By Rachel Sibande, Malawi Coordinator

It is expected that inefficient mechanisms for citizen engagement in service delivery are not unique to the home of the social accountability monitoring tool MobiSAM, in the Makana Municipality, South Africa.

A sister project to MobiSAM has thus been launched in Malawi in late August 2016. The project is being piloted in the three main cities in Malawi; Lilongwe, Blantyre and Mzuzu.

Titled, Mzinda meaning “My City” in Malawi’s populous Chichewa language, the project seeks to enhance citizen engagement with locally elected Councillors, City councils, the Electricity Supply Corporation of Malawi (ESCOM), and the Water Board on the delivery of essential services such as waste collection, sanitation, water and electricity at the local level.

Prior to the launch over 80 community block leaders from Blantyre and Mzuzu were trained on how to use the web-to-SMS platform through “Deepening Democracy” boot camps organised by the Story Workshop Education Trust. Twenty four of twenty six Councillors from Lilongwe City were also trained on how to use the Mzinda platform on 25 July, 2016.

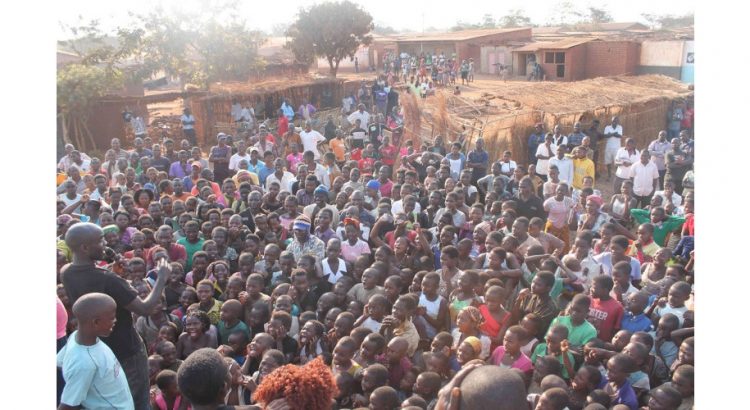

Nine community campaigns were conducted in prime locations within Lilongwe City such as Ntandire, Mtsiliza, Phwetekere and Senti. During these sessions, more than 1,000 citizens were sensitised on their rights to engage with duty bearers and service providers.

Citizens were also introduced to the web-to-SMS based Mzinda platform through which over 122 verified and approved SMS reports on service delivery issues were sent to the platform by citizens within the following categories:

- Water

- Electricity

- Sanitation

- Waste Collection

- Roads

Some reports translated from Chichewa to English read:

“Here in Mtandire; waste is dumped here but not collected.”

“There is no toilet in Kaliyeka Market”

A baseline study has been finalised to understand ways in which citizens currently engage with elected councillors, service providers and the city council. The baseline also seeks to understand how citizens use technology and gauge their willingness to use technology to engage with duty bearers and service providers. Comprehensive results from the analysis of data collected from the baseline study will be made available end of September, 2016.

Expectations

The ultimate test for any citizen engagement initiative lies in the rate of responsiveness from the state, duty bearers or service providers. It is expected that the purpose of such initiatives as Mzinda and MobiSAM is not only to amplify citizens’ voices, but to also enhance responsiveness and corrective measures. It is thus important to enhance the feedback loop from Councillors, city council and service providers rather than advocate for citizen’s voices alone. On the other hand; duty bearers have also expressed the need for citizens to use the platform productively and not for malice.

“I hope that Citizens will have the willingness to use the Platform constructively and resist from malice. I believe if Citizens report on real issues and with all honesty, we too as their representatives will be more than willing to assist,” said the Mayor of Lilongwe City Council, Willy Chapondera in his speech at the launch of the platform.

On the other hand, service providers such as the Lilongwe Water Board and ESCOM have fully embraced the platform. For example, Lilongwe Water Board has been posting water rationing schedules and tips on how to save water and prevent leakages through the platform. The board has also actively taken note of citizens reports on water issues and taken swift action where possible.

Lessons learned so far

One of the key lessons we have learnt so far is that, beyond access and use of technology; there exists a need to enhance citizen’s awareness of their rights to engage with duty bearers. This is corroborated by one of the key insights from the baseline study we conducted in the three pilot cities of Mzuzu, Blantyre and Lilongwe. The study reveals that 31.8% of citizens do not think their views matter or that they can make a difference at the local level; 65.3% have not participated in a community meeting. 80% have not reported any matter to their Councillor and 64.3% have not reported any service delivery issue to the city council, yet 72% are willing to use the mobile phone to engage with these entities.

We can therefore start making inferences which indicate that in the presence of technology, with low levels of citizen particiaption in local governance, there could be potential in the technological factors that will enhance citizen engagement. There are likely to be social, cultural and political factors that facilitate citizen participation. Several authors have alluded to this notion and suggested that social, political and cultural factors need to be considered when seeking to employ technological tools as way in which which citizens could engage with local government successfully, (Gigle & Bialur, 2014). Therefore it is important to note that part of the purpose of the research conducted by Mzinda is aimed at establishing which factors influence or inhibit the use of technology as tools for the engagement between citizens and local government. that influence or inhibit the use of technology as a tool for citizen engagement.

The beauty of having MobiSAM and Mzinda run side by side in the two different countries and contexts is that there are lessons to be learnt based on the different contexts and scope of the two deployments. A comparative analysis of the social, technical, economic, cultural and political factors that may enhance or restrict citizen engagement through ICTs in such different contexts may be relevant to the emerging discourse on ICTs for citizen engagement. Such lessons would be useful for academics, researchers, practitioners and technology developers to consider in subsequent deployments of ICTs for citizen engagement initiatives.

The Mzinda project is funded by the Open Society Initiative for Southern Africa. It is being implemented by Citizens for Justice and mHub with technical support from the MobiSAM Project at Rhodes University. Follow @mzindawanga on twitter, find us on Facebook or SMS your service delivery report to +265 888 242 063 and access the web platform at http://www.mzinda.com

First published on http://www.blog.mobisam.net/2016/09/mobisam-sister-project-launched-in-malawi/