To reclaim civic space, there are three key drivers that organizations must focus on, and three critical issues affecting local responses.

This article was originally published in this form on the OpenGlobalRights website, written by: Dhananjayan Sriskandarajah & Mandeep Tiwana

From attacks on human rights defenders to limits on civil society’s work, we are facing an emergency on civic space. As evidence from the CIVICUS Monitor suggests, threats to civic freedoms are no longer just happening in fragile states and autocracies, but also in more mature democracies. While there has been growing attention on how to respond to this phenomenon, we believe there needs to be more attention on underlying drivers and on supporting local responses. Civic space can’t be “saved” from the outside.

Many of the current restrictions on civil society are knee-jerk responses, sometimes pre-emptive, to popular mobilizations, a sad and unexpected result of the initial hope of the so-called Arab Spring. Of course, this pattern is not the only cause of growing constraints on civic freedoms. Repurposing of the global security discourse to curb dissent, restrictions on international funding for advocacy groups by nationalist leaders, and retreat from the international human rights framework using flimsy arguments of state sovereignty are all ways by which the rights discourse is being undone. While there are several drivers of civic space restrictions, three in particular are worth paying attention to, due to their cross-cutting nature and deep impacts.

1. The business of civil society repression

The impact of of mega-corporations and market fundamentalism in undermining civic freedoms cannot be overemphasised. Private sector influences are particularly clear in the area of natural resource exploitation by extractive industries and big agri-businesses when local, often indigenous, environmental defenders face retaliation for protecting natural resources from grabs by corrupt business and political interests. The assassination of award winning Honduran activist Berta Caceres and restrictions on the right to peaceful protest for those opposed to the Dakota Oil pipeline in the United States are examples of how of these challenges transcend global North-South boundaries.

2. A toxic mix of extremist ideologies

Civil society is also being increasingly targeted by extremists aiming to divide societies around narrow interpretations of ethnicity or religion. Civil society emphasis on diversity and social cohesion is derided as antithetical to nationalist cultural values and in some cases those speaking out against such projects are branded as operating at the behest of outside interests. In Europe, for example, civil society groups working on the rights of refugee and migrant populations are facing a backlash. In many parts of West Asia, women’s rights defenders have been attacked by armed groups seeking to impose puritanical religious doctrines on populations by arguing that gender equality is a Western construct. In South Asia, bloggers and journalists have been persecuted online and offline for opposing dominant cultural mores, while in Africa religious evangelists have linked up with like-minded groups on other continents to spur extreme forms of homophobia and attack defenders of LGBTI rights.

3. Retreat from democracy and multilateralism

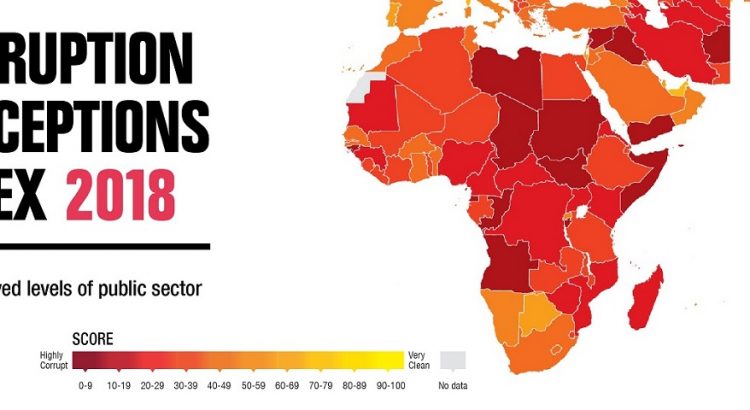

We’re also facing a crisis of moral leadership on the international stage which has led to a retreat from universal human rights values and is negatively impacting civil society. Degradation of civic freedoms and the emergence of “neo-fascist” politics in Europe and the United States have emboldened despotic regimes in countries such as Bahrain, Burundi, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Egypt, Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, and more, to attack dissenters and consolidate their power by manipulating electoral processes and state institutions. From the Philippines to Russia, Turkey and Venezuela, efforts are underway to silence dissent whereby repression against those who speak the language of human rights is becoming the norm rather than the exception.

Despite these challenges, placing local responses at the heart of efforts to reclaim civic space is critical. Based on conversations with civil society stakeholders on their present challenges, we have identified three under-researched but critical issues:

a. Resourcing resilience, close to the ground

In an era of growing linkages between rights oriented civil society organizations and the donor/philanthropic community, financial resources have become a key area of contestation. Only a tiny proportion of development assistance actually goes directly to civil society in the global South. Fickle donor priorities and excessive deference to whims of governments that restrict international funding have caused several smaller organizations to fold up. At the same time, bigger ones, which are more adept at marketing and meeting sophisticated accounting requirements of donors, are expanding. The organized civil society firmament has already started to resemble the market with big franchises edging out locally owned and rooted businesses. For example, an organization run by Syrian refugees in Turkey says they have experienced difficulties accessing international funding despite having much more relevant local knowledge than the international organizations that attract global donors. International donors should be mindful of how their red tape excludes community organizations that possess local expertise and have significantly lower overheads.

b. Beyond accounts-ability

Across the world, the legitimacy of organized civil society is being challenged on several fronts, from politicians demonizing them as disconnected special interest groups to social movements that see traditional CSOs as arcane at best and co-opted at worst. The usual ways in which CSOs demonstrate their accountability—through compliance with regulatory requirements and donor reporting are proving insufficient to convince skeptical politicians or publics. We thus need to move beyond just “accounts-ability” to enhanced transparency and dialogue with communities, not for the sake of checking a box but because they are key to making meaningful change. This shift could include things like people-centred decision-making, real-time adaptation to stakeholder needs, and nurturing the next generation of social change-makers. This form of accountability is not only about financial reporting and transparency to donors but about meaningful dialogue with affected communities and stakeholders, and keeping an eye on big picture outcomes to drive organizational decision-making process.

c. Standing together

Lastly, an energetic, civil society-led, global response is needed to counter attacks on civic freedoms. Many of us have done a good job of ensuring that the reality of closing civic space is on the international community’s radar, but efforts to push back against restrictions are often duplicative and uncoordinated. We must make clear that the enabling of civil society rights is an essential part of the defense of democracy. To do this, we need to form and work in progressive alliances, bringing together substantial masses of citizens and connecting classic CSOs, protest movements, journalists, trade unions, youth groups, social enterprises, artistic platforms and many other parts of the civil society universe.

A robust civic space can only exist within a functioning democracy, and thus safeguarding civil society also involves re-imagining more participatory models of democracy, with citizens at their heart. Seen in this way, the over-arching challenge is not a technical, short-term one of pushing back on attacks on civic space, but a longer-term political one of re-imagining a more participatory landscape where substantive democracy thrives.

***This article is an extract of an essay published in the 26th edition of the Sur Journal of Human Rights.