Civil society organisations providing humanitarian assistance to migrants and refugees are being targeted as the world faces a crisis of global compassion.

This alarming trend is one of the findings of the State of Civil Society Report 2019, an annual report by global civil society alliance CIVICUS, which looks at events and trends that impacted on civil society in the past year.

In one cited example, the Italian government prevented a boat operated by international medical NGO Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) from docking in Italy, leaving it stranded at sea for a week with more than 700 passengers, including unaccompanied minors. In the USA, organisations were prevented from leaving life-saving water supplies for people making the hazardous journey across the desert from Mexico.

“Civil society, acting on humanitarian impulses, confronts a rising tide of global mean-spiritedness, challenging humanitarian values in a way unparalleled since the Second World War,” said Lysa John, CIVICUS Secretary General.

“We need a new campaign, at both global and domestic levels, to reinforce humanitarian values and the rights of progressive civil society groups to act,” added John.

According to the report, in Europe, the USA and beyond – from Brazil to India – right wing populists, nationalists and extremist groups are mobilising dominant populations to attack the most vulnerable. This has led to an attack on the values behind humanitarian response as people are being encouraged to blame minorities and vulnerable groups for their concerns about insecurity, inequality, economic hardship and isolation from power. This means that civil society organisations that support the rights of excluded populations such as women and LGBTQI people and stand up for labour rights are being attacked.

As narrow notions of national sovereignty are being asserted, the international system is being rewritten by powerful states, such as China, Russia and the USA, that refuse to play by the rules. Borders and walls are being reinforced by rogue leaders who are bringing their styles of personal rule into international affairs by ignoring existing institutions, agreements and norms.

The report also points to a startling spike in protests relating to economic exclusion, inequality and poverty, which are often met with violent repression, and highlights a series of flawed and fake elections held in countries around the world in the last year.

“Democratic values are under strain around the globe from unaccountable strong men attacking civil society and the media in unprecedented – and often brutal – ways,” said Andrew Firmin, CIVICUS’ Editor-in-Chief and the report’s lead author.

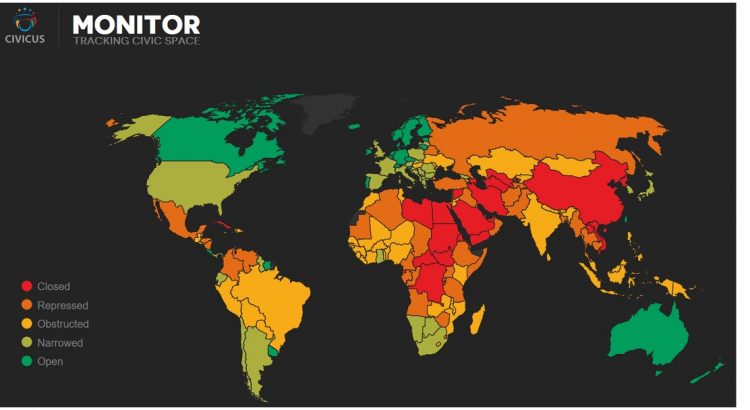

2018 was a year in which regressive forces appeared to gain ground. According to the CIVICUS Monitor, an online platform that tracks threats to civil society in all countries around the world, civic space – the space for civil society – is now under serious attack in 111 of the world’s nations – well over half of all countries. Only four per cent of the world’s population live in countries where our fundamental freedoms of association, peaceful assembly and expression are respected and enabled.

But the past year was also one in which committed civil society activists fought back against the rising repression of rights. From the successes of the global #MeToo women’s rights movement to the March for Our Lives gun reform movement led by high school students in the USA to the growing school strike climate change movement, collective action gained ground to claim breakthroughs.

“Despite the negative trends, active citizens and civil society organisations have been able to achieve change in Armenia, where a new political dispensation is in place, and in Ethiopia, where scores of prisoners of conscience have been released,” said John.

The report makes several recommendations for civil society and citizen action. The report calls for new strategies to argue against right-wing populism while urging progressive civil society to engage citizens towards better, more positive alternatives. These include developing and promoting new ideas on economic democracy for fairer economies that put people and rights at their centre. Notably, the report calls for reinforcing the spirit of internationalism, shared humanity and the central importance of compassion in everything we say and do.

Ends.

For an executive summary of the report, click here.

For the full report, click here.

Further reading:

Access the CIVICUS Monitor here and for more information on the latest CIVICUS Monitor ratings, click here.

About the State of Civil Society Report 2019

Each year the CIVICUS State of Civil Society Report examines the major events that involve and affect civil society around the world. This report looks back at the key stories of 2018 for civil society – the most significant developments that civil society was involved in, responded to and was impacted by.

Our report is of, from and for civil society, putting front and centre the perspectives of a wide range of civil society activists and leaders close to the major stories of the day. In particular, it presents findings from the CIVICUS Monitor, our online platform that tracks threats to civic space in every country.

For further information or to request interviews with CIVICUS staff and contributors to this report, please click here or contact: media@civicus.org