Background/context

With the outbreak of Covid-19, many governments’ health and basic service delivery systems have already been placed under considerable strain and across Africa, fragile health and economic systems are likely to face further planning and budgeting challenges now and in the aftermath of the pandemic. As a result, international financial institutions, private foundations and development agencies are pledging billions of dollars across the globe for governments to successfully combat COVID-19 and to cushion the most vulnerable populations from its socio-economic impact. The pandemic has also exacerbated pressure on the region’s public financial management (PFM) systems as well as exposed previous and ongoing corruption as more questions are being asked as to why health systems are weak/underprepared for the pandemic. At the same time, COVID-19 public health interventions are curtailing the abilities of citizens to exert accountability and oversight in many ways. Civic space and any efforts to expose COVID-19 related corruption are therefore vulnerable to clamp down. Local Transparency, Accountability and Participation (TAP) strategies are therefore critical to solving a lot of these challenges and to the future of better health & broader fiscal governance systems.

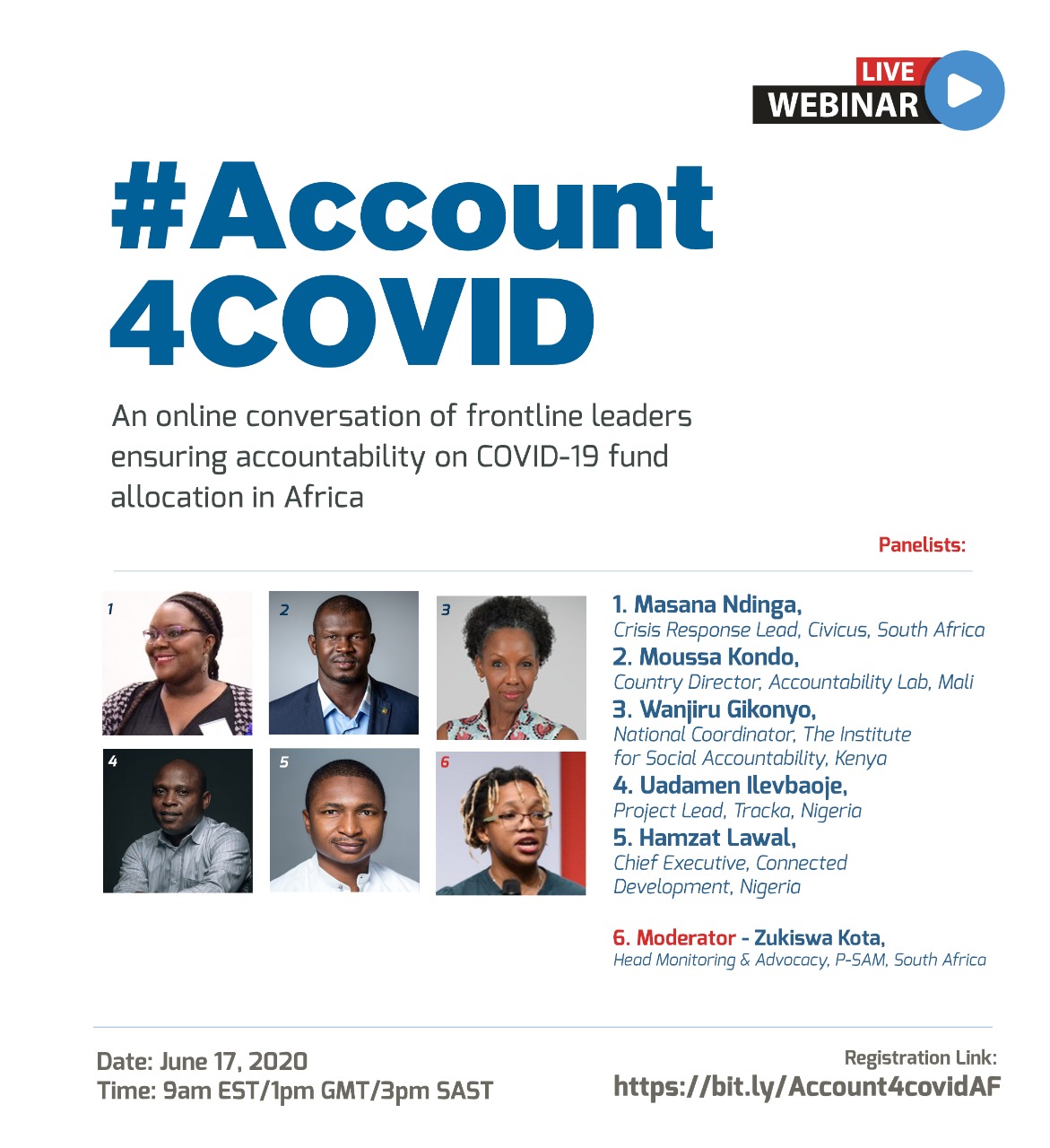

In April 2020, 8 organizations – Accountability Lab Africa & DC offices, African Freedom Information Center, AfroLeadership, BudgIT, CODE / Follow The Money Africa, the Public Service Accountability Monitor and Global Integrity – came together to collaborate on Account4COVID, an initiative that promotes and advocates for greater accountability, civic inclusion & transparency of COVID19 public allocations and expenditures.

Distilling our collective objectives

In May 2020, the above organizations scheduled a call with several organizations working in the field of fiscal governance transparency and accountability on the continent. These calls sought to explore how an initiative like Account4COVID could strengthen their local TAP strategies concerning publicly funded COVID-19 efforts. The consultative calls confirmed the need to gather actors from across the region to analyse the impact of COVID19 on fiscal governance and to exchange ideas and lessons for possible strategies to improve transparency, accountability and participation in the following key areas:

- Access to information & data to map and track allocation and expenditure of COVID-19 public funds ;

- Contracting & Public Procurement of goods and services for COVID-19 efforts ;

- The provision of health and basic services (water, sanitation and social welfare) especially for the poor and vulnerable communities ;

- Oversight, anti-corruption regulations and mechanisms.

The Account4COVID initiative plans to hold a series of webinar sessions to facilitate dialogue, networking and exchange between civil society organizations, and other change agents seeking to address TAP challenges and opportunities related to Covid-19 in their contexts.

Insights from the 1st webinar

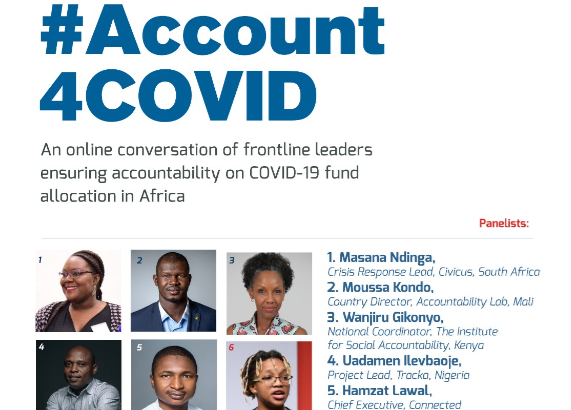

The first webinar on 17 June aimed to provide an overview of select COVID-19 related transparency initiatives across Africa. Additionally – the objective was to share, reflect and learn about some of the emerging opportunities and challenges concerning demands for transparency, accountability and participation in the use of COVID-19 related funds. The webinar attracted a diverse audience including advocates of open government, social accountability and open budgets in Africa and beyond. Speakers’ inputs and questions from the floor illustrated a range of important interventions to tackle novel (and not -so- novel) socio-economic challenges.

Hamzat Lawal, Chief Executive, Connected Development, Nigeria & Founder, Follow The Money International provided an update on its Follow The Money initiative which officially began in 2012 has been scaled up in recent months to a pan-African campaign which empowers other civic actors and oversight bodies with a technology application to map and track the COVID-19 donations in Kenya, The Gambia, Malawi, Cameroon, Zimbabwe, Liberia and Nigeria. In Zimbabwe, the technology application has also been designed to assist with contract tracing by mapping Covid 19 hot spots in Zimbabwe.

Masana Ndinga-Kanga, Crisis Response Fund Lead at CIVICUS in South Africa shared about impact of the South African government’s public health interventions on the right of civic actors to freely exercise oversight, organise, participate in decision making processes particularly around COVID-19 allocations & expenditures. She also highlighted how their transparency demands and participation in COVID-19 decision making processes as CIVICUS are designed to address the inequality gap within South Africa, in order to protect vulnerable communities from the pandemic. She also spoke about the unequal power relations between Western lending institutions and African governments which end up influencing fiscal priorities more than local voices.

Wanjiru Gikonyo, Director of The Institution of Social Accountability (TISA), Kenya talked about the lack of data, transparency and participation around current COVID-19 debt relief loan negotiations & other debt service offers from international financial institutions which is intended to free up resources for public sector health needs and other emergency spending. She pointed to the importance of debt transparency to mitigate against unmanageable debt levels which reduce domestic resource availability for future development priorities.

Moussa Kondo, Country Director for Accountability Lab, Mali presented on a recently launched Coronavirus CivActs Campaign (CCC) – a Citizen Help Desk to prevent misinformation and close data gaps including providing reliable data on Covid 19 donations and monitoring its expenditure by government as well as debunking pandemic myths and rumours. In the case of Mali, Accountability Lab has translated all the relevant data into local languages.

Uadamen Ilevbaoje, Project Lead for BudgIT’s spoke about the launch of a web based platform focused on COVID 19 building on their outstanding work with Tracka. The platform monitors Covid-19 donations given to the federal and state governments of Nigeria ranging from private and public, local and international organizations.

Learning and inspiration

The main takeaways and lessons learned from current COVID related TAP initiatives on the continent include

- COVID-19 has multiple revenue streams (private sector, foreign assistance, private donations, debt loans, national & sub national budgets & emergency funds). Technology has played a vital role in gathering all these different data sources in a ‘one stop shop’ and presenting it in an easily accessible way ;

- Aggregated data on its own is not useful, most campaigns aim to disaggregate the data as much as possible, and also gather data on the conditions and purpose of the funds in order to hold public officials accountable for the delivery of goods and services ;

- Civic actors need to pay equal attention to both transparency of allocated COVID-19 funds, as well as transparency around COVID related deferred debt payments and extension of additional credit ;

- TAP strategies have instrumental value and they are being used by civic actors to respond to contextual challenges such as inequality which has exacerbated the negative impact of COVID-19 on the lives of poor and vulnerable communities

- The political dynamics of unequal power relations and systems between international actors (donors) and local actors (national government) impact on fiscal governance priorities & decision making processes;

- Local TAP strategies are fighting the pandemic not only by providing financial data but by providing vulnerable communities with reliable information and facts about the virus. Countering misinformation, education and awareness raising tactics have thus been infused into the local TAP strategies.

At the end of the webinar, 45 attendees voted on the topic of discussion for the next Account4COVID webinar. Anti-corruption received the majority of the vote with 27%. 20% showed interest in the Socio-economic impact of COVID. The following topics: Contracting & Procurement, Expenditure Tracking, Health and basic service provision each received a vote of 13%. Access to information and Closing civic space each received a vote of 7%.

We hope to co-create a webinar series that is tailored to the needs of governance reformers. In order to help us do this, please kindly complete this short survey.

If you would like to participate in the next Account4COVID webinar and/or in the initiative more broadly please do feel free to reach out at acc4covid@gmail.com. This initiative, although limited to COVID19 and TAP in Africa, is open to any and all organizations interested in joining the initiative. Join the initiative and continue conversations offline!