To join this webinar, follow the link https://event.webinarjam.com/register/1/2o49qam

To join this webinar, follow the link https://event.webinarjam.com/register/1/2o49qam

Originally published by Transparency and Accountability Initiative (TAI) in June 2019

Funder grantmaking and learning practices are best when informed by grantee organization needs and experience, yet there are many factors that limit or even block this feedback loop. What kind of partnerships and meaningful change might be possible if both groups shared a mutual responsibility to convert traditional conversation nonstarters into a two-way dialogue?

To read further, the full report can be accessed here

Civil society organisations providing humanitarian assistance to migrants and refugees are being targeted as the world faces a crisis of global compassion.

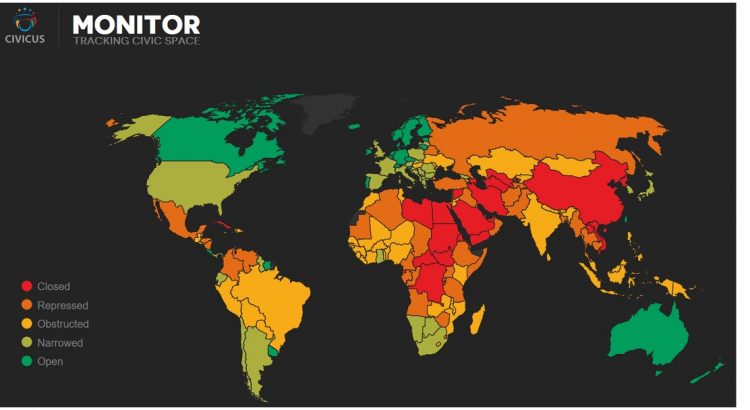

This alarming trend is one of the findings of the State of Civil Society Report 2019, an annual report by global civil society alliance CIVICUS, which looks at events and trends that impacted on civil society in the past year.

In one cited example, the Italian government prevented a boat operated by international medical NGO Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) from docking in Italy, leaving it stranded at sea for a week with more than 700 passengers, including unaccompanied minors. In the USA, organisations were prevented from leaving life-saving water supplies for people making the hazardous journey across the desert from Mexico.

“Civil society, acting on humanitarian impulses, confronts a rising tide of global mean-spiritedness, challenging humanitarian values in a way unparalleled since the Second World War,” said Lysa John, CIVICUS Secretary General.

“We need a new campaign, at both global and domestic levels, to reinforce humanitarian values and the rights of progressive civil society groups to act,” added John.

According to the report, in Europe, the USA and beyond – from Brazil to India – right wing populists, nationalists and extremist groups are mobilising dominant populations to attack the most vulnerable. This has led to an attack on the values behind humanitarian response as people are being encouraged to blame minorities and vulnerable groups for their concerns about insecurity, inequality, economic hardship and isolation from power. This means that civil society organisations that support the rights of excluded populations such as women and LGBTQI people and stand up for labour rights are being attacked.

As narrow notions of national sovereignty are being asserted, the international system is being rewritten by powerful states, such as China, Russia and the USA, that refuse to play by the rules. Borders and walls are being reinforced by rogue leaders who are bringing their styles of personal rule into international affairs by ignoring existing institutions, agreements and norms.

The report also points to a startling spike in protests relating to economic exclusion, inequality and poverty, which are often met with violent repression, and highlights a series of flawed and fake elections held in countries around the world in the last year.

“Democratic values are under strain around the globe from unaccountable strong men attacking civil society and the media in unprecedented – and often brutal – ways,” said Andrew Firmin, CIVICUS’ Editor-in-Chief and the report’s lead author.

2018 was a year in which regressive forces appeared to gain ground. According to the CIVICUS Monitor, an online platform that tracks threats to civil society in all countries around the world, civic space – the space for civil society – is now under serious attack in 111 of the world’s nations – well over half of all countries. Only four per cent of the world’s population live in countries where our fundamental freedoms of association, peaceful assembly and expression are respected and enabled.

But the past year was also one in which committed civil society activists fought back against the rising repression of rights. From the successes of the global #MeToo women’s rights movement to the March for Our Lives gun reform movement led by high school students in the USA to the growing school strike climate change movement, collective action gained ground to claim breakthroughs.

“Despite the negative trends, active citizens and civil society organisations have been able to achieve change in Armenia, where a new political dispensation is in place, and in Ethiopia, where scores of prisoners of conscience have been released,” said John.

The report makes several recommendations for civil society and citizen action. The report calls for new strategies to argue against right-wing populism while urging progressive civil society to engage citizens towards better, more positive alternatives. These include developing and promoting new ideas on economic democracy for fairer economies that put people and rights at their centre. Notably, the report calls for reinforcing the spirit of internationalism, shared humanity and the central importance of compassion in everything we say and do.

Ends.

For an executive summary of the report, click here.

For the full report, click here.

Further reading:

Access the CIVICUS Monitor here and for more information on the latest CIVICUS Monitor ratings, click here.

About the State of Civil Society Report 2019

Each year the CIVICUS State of Civil Society Report examines the major events that involve and affect civil society around the world. This report looks back at the key stories of 2018 for civil society – the most significant developments that civil society was involved in, responded to and was impacted by.

Our report is of, from and for civil society, putting front and centre the perspectives of a wide range of civil society activists and leaders close to the major stories of the day. In particular, it presents findings from the CIVICUS Monitor, our online platform that tracks threats to civic space in every country.

For further information or to request interviews with CIVICUS staff and contributors to this report, please click here or contact: media@civicus.org

I once worked on social accountability and now work on media development for the Center for International Media Assistance. When I bump into former colleagues, we update each other enthusiastically on our work, comment approvingly on the importance of our respective efforts, and part ways without the slightest clue as to how to collaborate.

After the Global Partnership for Social Accountability Global Partners Forum in Washington DC in October 2018, however, I’m convinced that we can no longer part ways without a plan, and that there is a mutual interest to do so.

Effective social accountability work makes good use of media, and effective media institutions are themselves both a platform for social accountability and a social accountability actor in their own right. Yet when media outlets are corrupt, captured, or unprofessional, they can equally be a hindrance to social accountability and a risk to engage with. But even quality journalism and social accountability initiatives are not likely to form a seamless union. Journalists value their independence and may be suspicious of being drawn into a “development” agenda. Furthermore, the civil society organizations committed to defending and strengthening the media frequently (with some notable exceptions) work in isolation from groups focused on the social accountability agenda. The relationship between media development, media, and social accountability is fraught, complex and still neglected. Some social accountability parlance is quite useful here for describing the untapped potential.

The Making All Voices Count Project (borrowing from more rigorous frameworks elsewhere by Anu Joshi, Jonathan Fox, and others) describes social accountability initiatives as ranging from functional to instrumental to transformative. Those categories can actually be applied to the limitations on how social accountability has engaged with media development.

Usually, social accountability initiatives engage with the media in functional and instrumental ways, but could pursue a more transformative agenda. A social accountability initiative that makes some effort to communicate with and through the press, and through new digital media platforms, could be said to have a functional relationship with the media – the bare minimum. A few move beyond this. At the GPSA, a multi-donor partnership managed by the World Bank, we heard two examples of projects that do so: Hivos’ “Open Up Contracting” program, and the Social Accountability Media Initiative, a project of the Aga Khan University Graduate School of Media and Communications in Nairobi.

The Open Up Contracting Program has built strong relationships with dedicated journalists, including by training them how to scrutinize and report on the government contracts that have been made public through the project’s efforts. This approach – treating the media as an autonomous actor – is likely to be more effective than purely functional social accountability projects that treat the media as a mere channel of dissemination. Still, the Open Contracting project does not have a remit to promote media development in its own right, and because of that its media engagement could be considered instrumental.

Social Accountability Media Initiative (SAMI) has a broader mandate. It also engages with journalists over the long term, bringing them together with farmers, school committees, and others engaged in social accountability projects without imposing an agenda or angle on the journalists. At the GPSA Forum, we heard about how SAMI has partnered with media outlets to ensure a community meeting with a provincial mayor in Rwanda – the results of local civil society mobilizing – was broadcast and covered in the local papers. Every SAMI activity also includes a “tripartite roundtable” with media, CSO, and government reps for “frank exchanges on obstacles to and opportunities for greater collaboration.”

So what does this all say about what a transformative approach to media development and social accountability looks like? In a transformative approach, civil society organizations not only bring the press to their community meeting, but ask the journalists about the challenges they face in their job and how civil society can help support the cause of the media freedom. Transformative means support to local media outlets that allows them to cover the relationship between government and civil society actors independently: for instance, by ensuring that the local government’s fiscal constraints are covered along with the activists’ demands. Transformative means all three institutions – local government, local civil society, local media – understanding each other’s limitations and challenges while slowly building shared values and mutual respect in their efforts to overcome them.

To be sure, there are still risks of co-optation in transformative approaches to partnership. Journalists are served well by their instinct to be skeptical, and social accountability actors will need some help to truly understand journalistic independence. Governments must also accept that critical public scrutiny comes with the territory of collaboration. But it’s a conversation well worth continuing.

Originally published on the GPSA website

Written by: Nicholas Benequista is Research Manager and Editor at the Center for International Media Assistance, an initiative of the National Endowment for Democracy.

*Photo description: Muyira, Nyanza, Rwanda, 17 October 2018. Reporter Regina Gacinya of Izuba Radio found eager interviewees at a community debate on agriculture practices. Credits: TR Lansner, AKU-GSMC

A recent civil society and government jamboree in Tanzania prompted some interesting reflections from Aidan Eyakuze, Executive Director of Twaweza.

This article was originally published on the ‘From Poverty to Power’ blog.

Who needs civil society organizations (CSOs)? If government does its job well, responding to citizens’ needs, delivering good quality services, safe communities and a booming economy, then what is the purpose of the diverse range of NGOs, trade unions, religious groups, community groups and others that make up civil society?

I was one of more than 600 people at CSO Week 2018 in Dodoma (Tanzania’s capital). We were there to both celebrate and debate the role of civil society in Tanzania. Lots of speakers from within and outside government spoke with almost universal praise for the role civil society plays. But not far below the collegial surface lurked a significant divergence of views.

The most important was conflicting views on the primary purpose of civil society. Government officials acknowledged the positive role of CSOs, but with a strong whiff of ambiguity about their value and scepticism about their integrity.

Government ministers and senior officials revealed a clear preference for CSOs focused on uncontroversial service delivery activities (providing healthcare or education or clean water), over those working on raising citizen voices and advocating for better policies. They said that CSOs that focus on service delivery are supporting the government as the people’s legitimately elected representative. They are giving people the help they need, and can attract additional aid dollars into the country for development. However, those CSOs that monitor and critique government, advocate for civic space and promote human rights, may in fact be pursuing foreign agendas or wasting resources by working in areas that do not resonate with citizens’ needs, such as public services and livelihoods.

I also heard many CSOs worrying that limiting their activities to providing services makes them little more than handmaids to government and reduces citizens to mere subjects. Championing the causes of social justice, equality, shared responsibility and rewards has them working to ensure people are free citizens.

But this is a simplistic, though long-standing distinction, and I think it misses the point. For the ‘uncontroversial’ services to be delivered well to those needing them most, civic space must, crucially and contentiously, be open.

Without freedom of information and expression, people will not know what they are entitled to. Nor will they be able to voice their opinion on the quality of services or bring other problems to the attention of decision makers. Without freedom of assembly and association, the gap between a distant and powerful government and an atomised population becomes almost unbridgeable. Without citizen participation, services rarely meet citizen needs and citizens feel  increasingly powerless and disconnected. Without inclusion, marginalised people are left even further behind. Without human rights and the rule of law, citizens have little protection from corrupt or bullying officials. Those who no longer trust that the game is fair stop trying to play and withdraw to the fringes.

increasingly powerless and disconnected. Without inclusion, marginalised people are left even further behind. Without human rights and the rule of law, citizens have little protection from corrupt or bullying officials. Those who no longer trust that the game is fair stop trying to play and withdraw to the fringes.

CSOs that work to protect and promote open civic space are also working to strengthen public services and improve people’s lives. We may be doing so indirectly, but our contribution is just as valuable and necessary.

I would go further to argue that even delivering services is a political undertaking. When people are healthier, better educated and have access to water, shelter and can make a decent living, they are more likely to ask for more and expect better. And delivering services has an impact on local power relations. A new well, for example, increases the availability of water for some, changes time allocation, especially for women, and alters patterns of ownership, income and social interaction in a village. Choices are inherently political.

So the question is not ‘are we for services or for social justice?’ The two are inseparable.

Bishop Stephen Munga, of the Evangelical Lutheran Church of Tanzania (ELCT) and Chancellor at  Sebastian Kolowa Memorial University expressed this point powerfully last week when he argued that “civil society gives rise to government itself.” “It is civil society that legitimately says whether government is good or bad, laws are good or bad. It is not for government or those in power to assess itself!”

Sebastian Kolowa Memorial University expressed this point powerfully last week when he argued that “civil society gives rise to government itself.” “It is civil society that legitimately says whether government is good or bad, laws are good or bad. It is not for government or those in power to assess itself!”

His assertions were both attractive, and unsettling. Who assesses us CSOs? I confess to leaving Dodoma with a nagging feeling that, as CSOs, we did not engage in some important self-reflection. Are we well-placed to deliver a vision of a healthy, wealthy, wise and just Tanzania? Are we trusted by those who we claim to represent and speak for? Are we legitimate in their eyes? How much are citizens engaged in our work, in shaping our priorities and activities, or are we distant, disconnected and self-righteous? And how much are we really contributing to improving social justice overall? Could we do more?

These questions warrant really good answers. Such deep self-reflection can only be healthy for the sector, and for the wider community which we serve. We should not shy away from it.

It should come as no surprise that government and civil society have different views on what the sector should look like, or on the relationship between services and rights. It is only proper that a combination of tension and collaboration should exist, as one party seeks to maintain social order and the other to promote social justice. A society without such tension would slide into decline and decay.

So what is civil society for? It is to improve public services and people’s livelihoods. It is also to raise citizen voices and protect civic space. And it is even, on occasion, for disagreeing with government. I am sure that doing these things makes us all stronger. We will all be better off as a result.

This article was originally published here

Written by Kimani Njogu, originally published as part of a series of essays: Examining Civil Society Legitimacy

Kenya is often lauded for promulgating one of the world’s most liberal constitutions. Passed on August 27, 2010, it radically devolves power to county governments, ensures the separation of powers, and entrenches a progressive bill of rights. This would have been impossible without the work of robust, courageous, and independent civil society organizations (CSOs). Civic actors first laid down their recommendations for constitutional reform in the document “Kenya Tuitakayo” (The Kenya We Want), which became a crucial resource for the Constitution of Kenya Review Commission. After former president Daniel Arap Moi asked at a public rally what “Wanjiku”—a common name, meant to refer to ordinary Kenyans—could possibly know about constitution-making, civil society appropriated the term, popularized it, and turned it into an organizing symbol for the constitutional reform process.

Throughout the 1990s and 2000s, the legitimacy of Kenya’s civil society stemmed from its engagement with key issues that all citizens cared about. Following the liberalization of political space, CSOs undertook extensive civic education on basic rights and how public sector corruption affects citizens’ access to health, food, shelter, and education. They provided a link between citizens’ daily lives and the people who occupied leadership positions in government. Faith-based organizations offered sanctuary to those targeted by the state and used their platforms to speak about the need for political change.

Yet over the past ten years, the political climate has changed. A number of politicians have publicly questioned the legitimacy of CSOs, especially those engaged in governance and human rights. Some have referred to civil society as “evil society,” a label used to rationalize new restrictions on civic space. These attacks have their roots in the 2007–2008 electoral crisis. In the aftermath of the violence, CSOs worked closely with public institutions and international agencies to collect evidence against those suspected of having orchestrated unrest. When the International Criminal Court (ICC) indicted several senior political leaders, the latter used ethnic identity and nationalism to mobilize their followers to fight back. State functionaries accused CSOs of working with foreigners to undermine the sovereignty of the nation. Although the ICC later dropped the cases, the “foreign agent” label stuck. It has undermined CSOs’ relationship with the wider population and weakened their claims to legitimacy. Political elites’ incessant instrumentalization of ethnic identity has further exacerbated the problem. They have tried to paint civil society as ethnically biased in order to erode public trust in their positions. As a result, it has become harder for civic actors carry out their work.

Kenyan CSOs also have been tainted by the perception that they are partisan political actors. This perception is particularly damaging in a context of high ethnic polarization where oversight institutions are weak. During the 2013 and 2017 presidential elections, the incumbent government accused some civil society actors of siding with particular opposition candidates and political parties. This perception stemmed from the fact that parts of civil society voiced their opposition to politicians who had previously been indicted for crimes against humanity by the ICC and who were viewed as intolerant to the civil liberties enshrined in the constitution.

Perceptions of partisanship have not only alienated some civil society stakeholders but also fostered ideological divisions within civil society. Of particular concern, for example, are tensions over electoral justice between development and peace-building groups on the one hand and human rights organizations on the other. Whereas the latter emphasize that electoral justice is essential for sustainable peace, the former have argued that in a highly polarized nation like Kenya, electoral justice can only be realized in a stable, calm, and nonviolent atmosphere. The fact that some human rights actors have used labels such as “peace-preneurs” to categorize organizations working to prevent election-related violence does not help build the legitimacy of the sector. Instead, divisions among CSOs only serve as fodder for attacks by the political elite.

In the current hostile political context, public officials have also exploited administrative rules to crack down on civil society. As a result, it has also become crucial for all organizations to ensure they are properly registered and meet all statutory requirements. In August 2017, for example, the NGO Coordination Board set out to deregister the Kenya Human Rights Commission. It also instructed the Directorate of Criminal Investigations to shut down the operations of the African Centre for Open Governance (Africog) for allegedly operating without a registration certificate. Individuals from the Kenya Revenue Authority raided Africog’s offices over clams of tax noncompliance. Although these allegations were later debunked through the judicial process, it is noteworthy that the state had launched the attack based on alleged noncompliance with legal and regulatory processes. Kenya has hundreds of community-based organizations that generally are viewed as highly legitimate because they are known by their immediate constituencies, from the household to the village. They speak the language of their communities and undertake activities viewed as local priorities. These organizations can easily lose their legitimacy if they are no longer viewed as accountable and transparent in their work.

Kenyan CSOs face a delicate balancing act as they try to build legitimacy while facing continuous attacks by the state. To survive, they should continue to demand accountability in the use of public resources by leaders and public officials. Internally, they ought to build governance and monitoring and evaluation systems that enhance their transparency and advance their mission. They also have to engage with the issues that directly affect their constituencies. When the state seeks to limit civic space, our stakeholders in the communities we serve ought to be our first line of defense.

Kimani Njogu is the director of Twaweza Communications (Nairobi), an arts, culture, and media institution committed to freedom of expression. Dr. Kimani is Chair of the Board of Trustees at the Legal Resources Foundation Trust and Content-Development Intellectual Property (CODE-IP) Trust. He is a recipient of the Ford Foundation Champion of Democracy Award and the Pan-African NOMA Award for Publishing in Africa.

An interview with Nathaniel Heller, Results for Development. Originally published here

By now, I think we can all agree that we’ve reached the peak of big data, returned to base camp, washed our kit and started planning the next climb. For a short while, big data was presented as the solution to all our problems. The premise was simple — collect more data, make it look pretty, push it out and people would start using it to make decisions that would end poverty, expose corruption and reverse unsustainable exploitation of our environment.

But things didn’t work out that way. In the rush to deliver data to the people, the people forgot the people. Bigger didn’t mean better and data dashboards became graveyards filled with withering flowers.

Data designed for the living need to be centered around humans and the unique needs we all have. Results for Development (R4D) is an organisation that puts the users of data at the centre of all their efforts to achieve sustainable progress in health, education and nutrition. I spoke to Nathaniel Heller, Executive Vice President for Integrated Strategies at R4D to learn more about their user-centric approach to data and the importance of thinking ‘small’ when it comes to helping people make better use of data.

“There’s a mistaken belief that if we present people with pretty data, good decisions will happen,” said Nathaniel. “But data isn’t the only input into decision-making. You have to consider the capacity of the governments or organisations involved to carry out the task they’ve been given and what hurdles they have to overcome. The use of data in decision-making is much more nuanced than simply making more data available.”

R4D works with change agents to find long-lasting solutions. Focusing on identifying important and transformational data, R4D will only invest in data tools if there’s a strong case for it. “Sometimes it seems like there’s a data problem,” explained Nathaniel, “but once you start talking to people about what they need, you’ll see there’s another underlying issue that has nothing to do with the data.” It’s these underlying issues that R4D’s user-centric approach to problem solving uncovers.

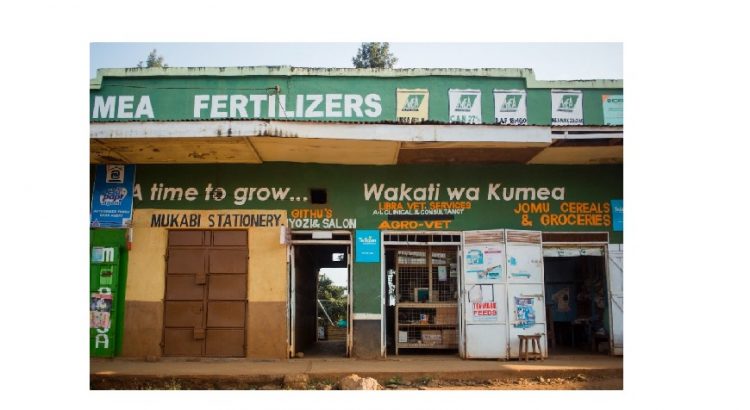

To illustrate his point, Nathaniel told me about a current project that he’s particularly excited about. R4D spent about year poring over all different kinds of country-level agricultural data in several African countries to identify opportunities for agricultural transformation — the kind of macro shift that has the potential to lift tens of millions out of poverty and address nutritional needs. The initial idea was to create a dashboard and open up access to the data, assuming this would motivate national political leaders to embrace a push for change. But when R4D spotted an opportunity in the data (only a tiny percentage of smallholder farmers in Kenya use inorganic fertilizer), they decided to shift strategies.

In Kenya, getting the right fertiliser can be an expensive and time consuming effort for farmers. A half-day journey to the market might end with the purchase of the wrong fertilizer, or worse, a counterfeit product that does more harm than good. R4D and their partners at the Local Development Research Institute saw an opportunity to create a service that would help people locate the right fertiliser, for the right price, from a location within easy travelling distance.

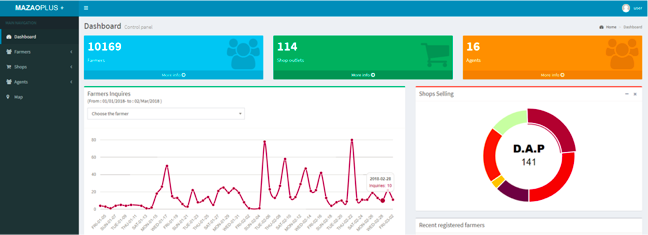

MazaoPlus+, an SMS service for farmers (and its accompanying Android app used by field agents to onboard users) was built in just two weeks. More than 10,000 farmers have already subscribed to receive fertiliser advice via their phones. We have to wait until harvest time to see if the app has helped improve yields through improved access to fertilizer, but Nathaniel sees a great potential in this service, both in terms of the agricultural impact and potential for scaling up into something bigger.

“The Kenyan fertiliser SMS service is a good example of our methods where we emphasise fit-for-purpose principles when it comes to leveraging data; we often focus on the small data, not the big data,” said Nathaniel. “We thought it through first and built second; which is exactly how every project should go.”

Small data is a term that’s never been as popular as big data but it describes data that are presented in a volume and format that’s easy for humans to access and use. Whereas reams of big data can be collected and processed by artificial intelligence, small data is curated by humans for other humans. The personal touch of small data ensures the solutions being developed to improve education, healthcare and agricultural systems are meeting a real need and supporting change.

On their website, R4D speaks about “artificial solutions”, whereby resource-constrained governments find themselves forced to adopt data-for-development tools without adequate planning or data uptake strategies. I asked Nathaniel how these artificial solutions could be avoided. “When someone proposes a solution, you start by asking, ‘has anyone (other than the funder) asked for this?’” said Nathaniel. “If they say yes, good, but if not you need to dig deeper and ask more questions. Structured interviews with potential users provides lots of interesting feedback that will help you understand their needs and pain points, enabling you to determine if the root cause of their problems really is a data issue, or something else entirely.”

Talking and listening to your users to learn what they need is common sense but it’s always worth reminding ourselves why. As Nathaniel and R4D have shown, understanding the needs of people and developing a solution that’s tailored to them will always be more effective than taking a ‘store-bought’ solution and moulding it to their situation. After all, one-size-fits-all rarely fits anyone. When — and only when — data is identified as the true issue, every care must be taken to curate it and package it in ways that are accessible, usable and useful for the users. These are principles Vizzuality shares with R4D, so let’s think small when it comes to big data.

By the International Budget Partnership

A number of multistakeholder initiatives (MSIs) have brought together governments, civil society organizations (CSOs), and private sector firms to hash out a variety of difficult governance issues. Initiatives such as the Open Government Partnership, the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative, and the Global Initiative for Fiscal Transparency work to encourage transparency and accountability reforms in a rapidly expanding number of countries around the world.

But while the breadth of these MSIs is inarguable, how deep do reforms really go? What tangible changes are they driving at the country level? These are some of the questions that Dr. Brandon Brockmyer of the Accountability Research Center has been investigating. We recently spoke to Brandon about his research.

IBP: Can you give us a quick outline of your findings in terms of the effectiveness of MSIs?

Brandon: Overall, what I found is that global MSIs are quite good at encouraging participating governments to proactively disclose information about their activities and performance, even in cases where governments are disclosing this information for the first time. However, MSIs are notably less effective at encouraging participating governments to become more responsive to requests from citizens for information that they are not already publishing. This allows governments to retain control of the agenda, deciding what information to disclose.

MSIs help to improve proactive government transparency when two core conditions are in place: First, nongovernmental actors (i.e., civil society and the private sector) must be treated as full and equal partners in MSI decision making and implementation. Second, participating civil society organizations must have the technical expertise to steer disclosure in the right direction, as well as the resources to regularly attend meetings.

IBP: One of the interesting findings is that it seems MSIs are quite effective at advancing transparency, but broader improvements to accountability so far have been more elusive.

Brandon: Currently, global MSIs are designed to tackle transparency directly, while most of these initiatives address accountability only indirectly. This approach seems to assume that there is a straightforward, linear relationship between the two. I think my research findings support a more general consensus emerging in the field that transparency gains alone are unlikely to drive gains in accountability. Disclosed information needs translation, aggregation, benchmarks, and simplification to be useful to potential users. Demands for greater accountability require collective action that can be difficult to organize, especially given that civil society groups vary across regions, sectors, and funding levels and often have different priorities when advocating for government action. And even if these groups can come together to make coherent demands, citizen voice alone may not be an effective channel for changing the incentives of public sector actors, or for gaining greater influence over public resource allocation.

If global MSIs want to tackle the challenge of accountability more directly, their activities probably need to be more purposefully embedded within existing national pro-accountability coalitions. I think this could be done in several ways:

IBP: Many of IBP’s civil society partners are also trying to push their governments to improve transparency and accountability. Did you find any evidence where CSOs were able to use MSIs to advance their agendas?

Brandon: Yes, but it really depends on the specific agenda. CSOs that are already working toward greater government transparency will often find natural allies in the government and private sector by engaging with global MSIs. In these cases, MSIs offer a powerful way to advance their agendas. However, for those CSOs that value transparency primarily as a tool for advancing a broader social or environmental agenda, participation in a global MSI may be a costly distraction. In fact, I found that participating governments sometimes use MSIs to “openwash”— that is, to project a public image of transparency and accountability, while maintaining questionable practices.

IBP: IBP engages with initiatives like OGP and GIFT, particularly at the global level, while at the same time supporting many local CSOs at the national and local level. What insights do you have about bridging these big global movements with the nitty-gritty challenges that CSOs face on the ground?

Brandon: I think it’s critical that CSOs considering engaging with global MSIs have a realistic sense for how MSI activities and outputs might fit into their own broader reform strategies. Conversely, it’s equally important that global MSI architects work to tailor activities and outputs to fit the needs of pro-reform actors in participating countries.

IBP is well placed to inform both sides of this equation. IBP can educate CSOs about how global MSIs work, so the CSOs can make informed decisions about whether to get involved. If CSOs decide to participate, IBP can also serve as an invaluable resource for effective strategies and tactics for using global MSI processes to achieve their domestic goals. Simultaneously, IBP can use its influence within these global initiatives to advocate from a CSO perspective for MSI membership rules, events, and training opportunities are optimally geared toward producing the types of transparency and civic participation that CSOs identify as critical for their broader reform strategies to work. Nevertheless, it’s also important to remember that the reform process is likely to unfold somewhat differently across various contexts. As a result, IBP can guide MSIs toward offering participating members a more useful toolkit, but MSIs must still avoid being overly prescriptive.

Admittedly, this is a tough balance to strike. But by embracing the fact that not every global MSI will be a good fit in every context, IBP can help global MSIs improve their credibility, and help national and local CSOs avoid pointless opportunity costs.

This article was origninally published by the IBP here

There is a clearly a surge in social accountability initiatives across the globe today. From informal expressions at the grassroots to entrenched voices in corridors of power, the social accountability multiverse has become stronger and diverse. It wouldn’t be an exaggeration to say that we are indeed witnessing the rise of an ‘audit society’ that animates the spectrum between confrontation and collaboration in citizen’s engagement with the state. The proliferation of toolkits and manuals embellishes this trend as social audits and scorecards have become commonplace parlance for civic activists, policy wonks and academics as they line up an impressive array of data to hold the state to account. However, viewed from the trenches of day-to-day encounters with social accountability, some notes of caution need to be flagged:

1) Primacy of technique over politics: ‘Bring politics back’ is an oft-quoted plea that is heard at the closure of every learning and sharing event on social accountability. Though some excellent conceptual writings exist on the rationale and approaches to acknowledge politics, there is clearly a knowledge gap on praxis. This gap becomes accentuated when projects finish their shelf lives and local interlocutors are left dealing with unplanned political aftermaths. What we need is not just the ‘why’ and ‘what’ of navigating politics, but the ‘how’ too. There is also the bias of working with executive ‘accelerators’ – reformist executives who push the frontiers of constructive engagement and deliver high quality impacts on pilot projects. But the reason why these ripples of change never result in a transformative wave is because politics is often viewed as a problem best avoided. We need to acknowledge that any change sans the inconvenience of politics is bound to be short lived. Working with politics and programming with sensitivity to political ecologies means more flexibility in design and implementation. This is where contemporary discourses on ‘Doing Development Differently’ are opening up new opportunities and pathways.

2) Tyranny of tools: Social Accountability tools like public hearings, scorecards, report cards and social audits have played a major role in bringing rigor to discourse and praxis, by moving the frame of reference from the anecdotal to the evidential. However, projects driven by the novelty of applying tools run the risk of not just undermining sustainable impacts, but paving the way for a far more serious erosion of trust and acceptance. Tools have a tendency to trade efficiency over inclusion, and participation over representation. There is also a case for ensuring quality. As an evolving field where theory consistently lags behind practice, it is critical that the field of practices is constantly reviewed, reflected upon and improved. Finally, there is the issue of local capacities. Applications of tools in rural areas often rely on external agents to play the role of interlocutors, but seldom do legacies and capacities get left behind for continued actions by local interlocutors.

3) Interrogating civil society: A dominant theme in the discourse and praxis of accountability is the emphasis placed on the role of civil society as the vanguard of change. There are genuine concerns that the sector is fast losing its rootedness and legitimacy –a schism grows between genuine informal social movements and formal organized civil society. One, exhibiting the vigor of confronting and embracing the politics of governance and the other, seen as obsessed with the rigor of getting the method right. We need to honestly interrogate our understanding of civil society organizations and widen our focus to bring in new, unseen but genuine champions from the cutting edges. A considerable proportion of existing civil society proponents of accountability often tend to be urban centered, and speak a language that appeal to our funding imperatives. We need to empower and enrich the language that has the credibility and endorsement of the basic constituency that we seek to address – citizens, especially the disadvantaged.

4) Seduction of contestation: Rights-based social mobilization sometimes leads to an unintended consequence – spiraling expectations. When amplified voice encounters weak responses from the state, ‘rude accountability’ manifests. The grammar of engagement changes swiftly to a confrontational mode. In social contexts where power asymmetries are accentuated, these confrontations can take very violent forms. There is a case for calibrating social accountability initiatives to match state capacity. In contexts marked by a trust deficit between state and citizens, it may be prudent to focus on trust building exercises as a starting point. The other issue is of public dissemination. Should one go for a big bang release of the findings from a social audit, thereby securing a guaranteed news coverage? Or, should the state be allowed to frame its responses and then go public with the findings and responses? To strengthen principles of constructive engagement, closing the feedback loop in the public domain becomes a critical factor. Voice needs an ear to respond.

5) Rethinking evaluation: It is near impossible to engineer transformative changes given the short project cycles of social accountability initiatives . End of project evaluations can seldom provide meaningful insights. What the field of social accountability needs are longitudinal studies that explore questions related to sustainability and uptake of reported successes. In particular, five aspects could be emphasized: (a) Extent of multi stakeholder engagement; (b) Width of citizen involvement, especially aspects of inclusion; (c) Long-term partnership among stakeholders; (d) Legal or institutional recognition of civil society engagement; and (e) Extent to which processes generate compliance and provide deterrence. Rather than focus on narrowly defined outcomes, evaluations should dwell into process indicators that reveal if critical pathways and enablers are set in place.

6) Illiberalism and social polarization: Perhaps the greatest challenge for social accountability initiatives is the growing popularity of illiberal electoral democracies and, in parallel, the deep social polarization that is tearing up fragile social fabrics. Leaders with divisive agendas and populist outlooks, aided by manipulated (and at times, completely fake) news are posing a grave threat to democratic institutions. There is also the distinct disconnect between the informed public and the mass public in terms of their expressed trust in institutions. All these have substantive repercussions on the way we imagine and operationalize social accountability. We need to focus on activities that build bridging social capital – locating actions that result in enhanced inter-group collaboration. The role of traditional media – once the trusted ally and champion for accountability – needs to be evaluated given the ubiquitous spread of social media. Rather than lamenting the loss of old spaces, the strategy should be to appropriate the new ones.

To sign off: Social accountability is recognition that there exists a lack of engagement with the public institutions that are so critical to our daily lives, a lack of influence in decision-making and more importantly, a lack of voice for expressing our needs, concerns and demands. We believe that social accountability approaches enable citizens, especially the voiceless and the powerless, to engage with state institutions in a proactive and constructive way to demand and exact accountability and responsiveness. This moral high ground of the concept and praxis of social accountability needs to be protected and nurtured.