By Jeff Thindwa, Program Manager, GPSA.

First published on the GPSA website.

By 2030, almost half of the world’s poor will be concentrated in countries affected by fragility, conflict and violence. It’s easy to associate these problems with only poorer countries, but in fact they affect a broader range of countries, and yes, middle income countries too. And, increasingly, they cross borders. Beyond the threats of terrorism, conflict and violence, poor public services and economic livelihoods have led to mass migration and forced displacement, trapping growing numbers of innocent people in vicious cycles of deprivation. Consider how the Syrian refugee situation has spilled over beyond the Middle East, and the current famine in South Sudan, which is impacting approximately 100,000 people, with millions of lives at risk in the region if we do not act quickly and decisively.

As has been long argued, addressing the challenges of fragility, conflict and violence calls for measures along the whole continuum of emergency assistance and long-term development. We need to support affected communities not only with the delivery of vital services, like water or healthcare, but also enable people to be more resilient and to rebuild the social fabric. More important, perhaps, we must invest in prevention. We must also provide the kinds of support that enable governance to include and involve citizens, and to respond to their needs and preferences.

The lack of accountability and the loss of citizen trust are some the drivers of fragility and conflict. It is often said that accountability is the cornerstone of good governance. Among the different ways to strengthen accountability and improve how governments work is social accountability, an approach that relies on citizen engagement. Social accountability mechanisms have features that make them potentially suited to both tackle the drivers of fragility and enable countries to improve their governance. In this respect, the Global Partnership for Social Accountability (GPSA) is working to integrate social accountability in the World Bank’s response to these challenges.

As part of this effort, last month the World Bank hosted a roundtable, “Engaging Civil Society in Situations of Fragility, Conflict and Violence,” featuring Kristalina Georgieva, the World Bank’s Chief Executive Officer; Debbie Wetzel, Senior Director of the Governance Global Practice; Saroj Kumar Jha, Senior Director for the Fragility, Conflict and Violence Group; Ede Ijjasz-Vasquez, Senior Director for the World Bank Group’s Social, Urban, Rural and Resilience Global Practice; and members of the GPSA’s Steering Committee. The roundtable tackled important issues related to the role of social accountability in situations of fragility, which includes bringing the voices of citizens into government, enabling citizens to monitor and provide feedback on delivery of services, and helping to build trust between citizens and governments.

Preventing Crises

The challenges in fragile settings can range from weakened institutions, broken public services, frayed social relationships and a weak civil society. Rebuilding of societies can cost a lot, and take a very long time. So, Kristalina Georgieva hit the nail on the head when she said, “The best way to deal with humanitarian crises is to not have them in the first place. We must build resilience for individuals, families, communities and countries.” To build stability, it’s clear that development institutions such as the World Bank need to engage early to address emerging risks. Our response needs to be comprehensive and sensitive to each context.

Saroj Kumar Jha asked during the roundtable, “Can we use development tools differently to prevent conflict before it turns violent?” That’s where the GPSA fits in, as we see social accountability as part of a sustainable approach to overcome fragility. Saroj announced the new partnership between his group and the GPSA, committing US$1 million from the State and Peacebuilding Fund (SPF) to support resilience and mitigation efforts initially in Guinea, Nepal, Niger and Tajikistan.

In order to ensure what we do is sustainable, we have to take up approaches that lay the ground for longer term institution building, with strong emphasis on engaging citizens to build political support, promote social cohesion and strengthen resilience. Experience has also taught us to pay attention to inclusion across institutions: public and private, formal and informal, whether governments, community groups and development organizations.

For instance, in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), we are supporting CORDAID to improve health service delivery by strengthening the ways in which citizens interact with health authorities, like strengthening Health Facility Committees that act as a mechanism through which citizens can interact with service providers. The health sector in DRC, as in many fragile settings, is marred by inefficiencies, insufficient funding, poor infrastructure, limited accountability and weak institutional capacity. Another example is in Sierra Leone, where the GPSA is supporting the CSO, IBIS, to monitor the effective utilization of post-Ebola recovery funds. The GPSA is working to ensure that the resources provided under IDA18 are used effectively in fragile environments, and CSOs are vital partners in many of these efforts.

The promise of social accountability

We have also learned that the challenges of engaging in fragile contexts — where the rule of law, security, space for dissent, and basic trust between citizens and governments cannot be taken for granted — call for innovation and adaptation in our approaches and tools. The good news is that a great deal of innovation has taken place in recent years to improve how citizens are engaged in the development process, supported by civil society organizations and, in some cases, private sector actors.

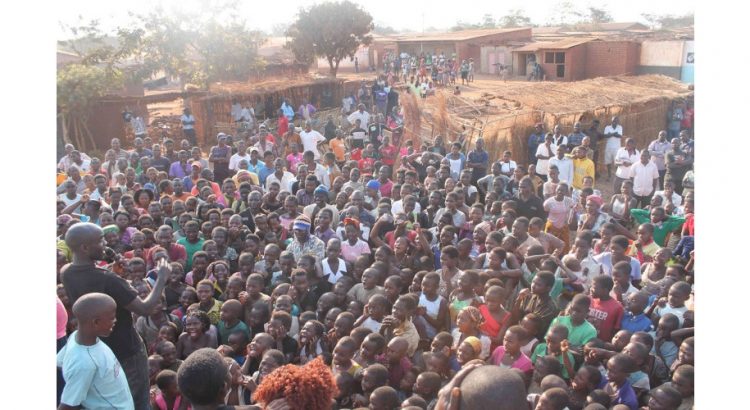

When it comes to operating in fragile settings, CSOs have advantages that have been widely recognized, even if experiences differ across contexts. With the right kind of support, CSOs can be effective mediating agents. They often work directly with the most vulnerable people, using participatory methods that include citizens, to hear their voices and make them a part of the solution. They are mostly present in remote or isolated parts where others may not be able to reach; are often more agile in their practices; and, increasingly, a lot of them have strong technical expertise including the use of information and communications technologies.

As Debbie Wetzel said at the roundtable, “It is important to build the connectivity between governments, civil society and other organizations on the ground. We need to use the tools at our disposal, including the GPSA, to continue to open the space and emphasize that engagement leads to policy effectiveness and better results.” CSOs also have a potentially significant role as third party monitors of donor operations in fragile states — a point that Saroj Kumar Jha also made when he explained the priorities of the SPF, which finances innovative approaches to state and peace-building in regions affected by fragility.

Finally, a theme that was echoed at the roundtable, and a key lesson from social accountability practice, is that context matters. Well, nowhere is this more relevant than in fragile states, even if we admit we are continuously learning about what works and doesn’t and under what conditions. A little bit of humility doesn’t hurt! The international development community has been called upon to do more in these challenging settings using the full range of tools at our disposal. But we can’t forget that the central focus is the people. Our approaches must keep them at the center, listening, including, involving them — ensuring all this benefits them!