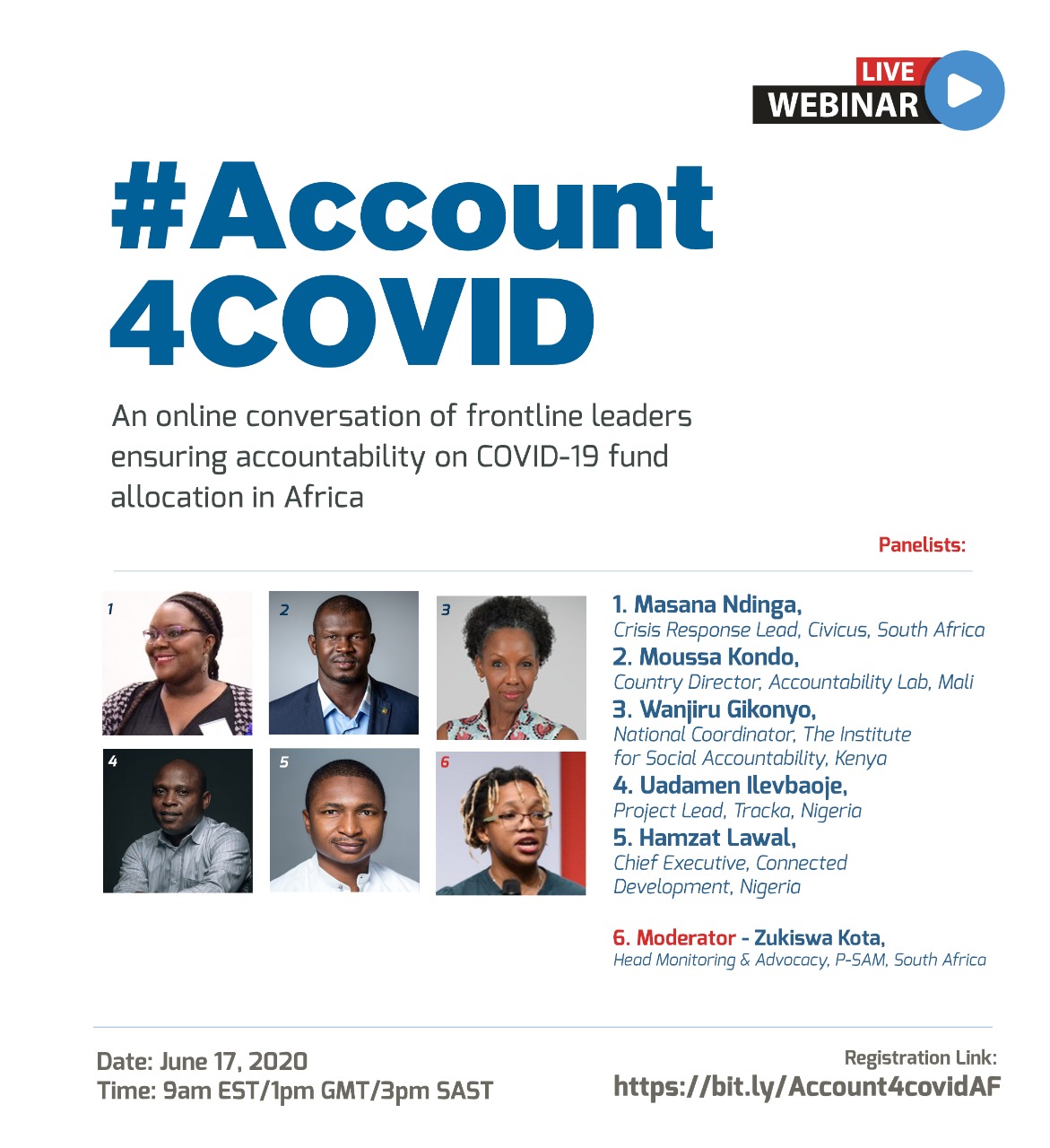

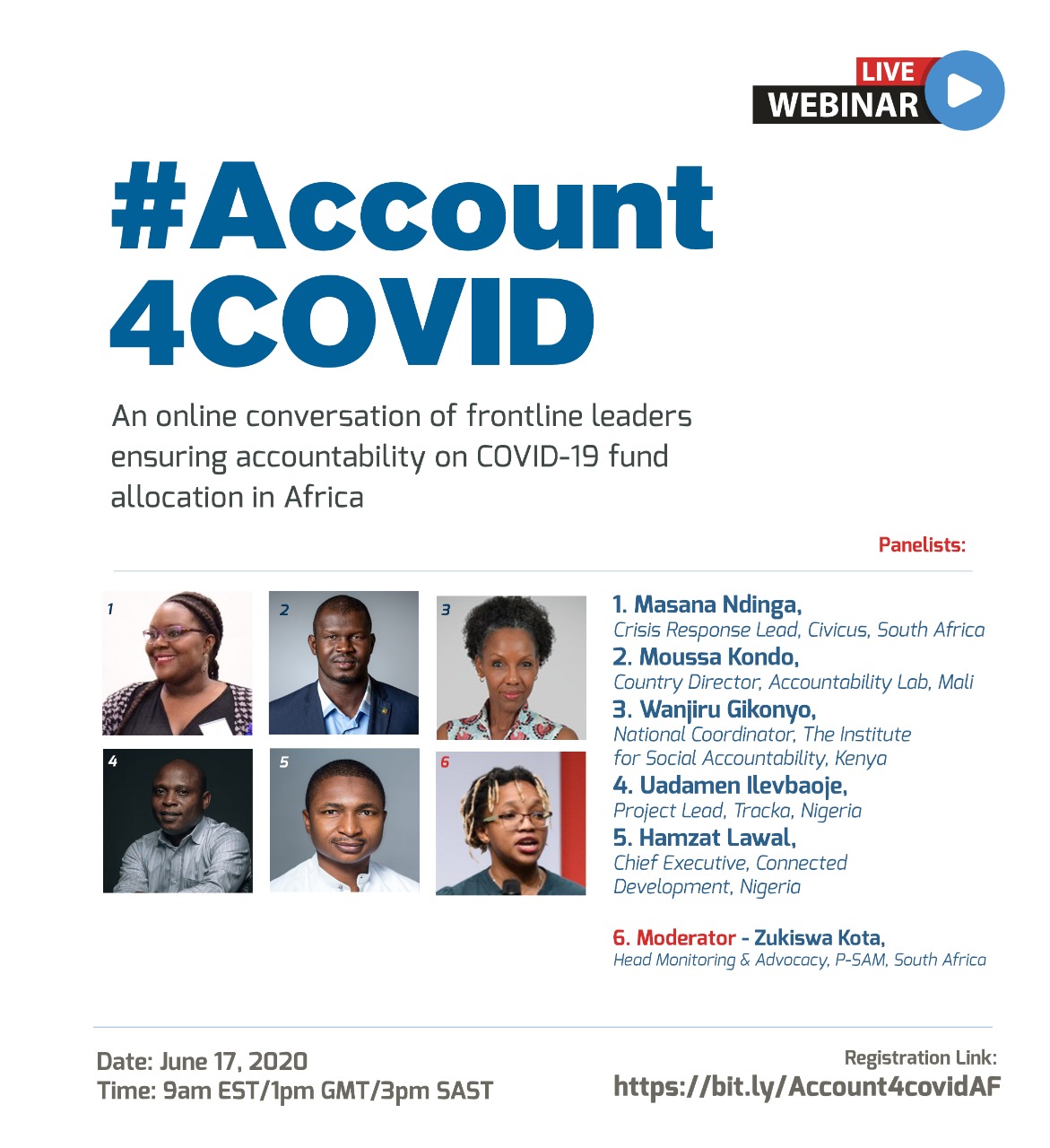

An online conversation of frontline leaders ensuring accountability on COVID-19 Fund allocation in Africa. To join follow this link https://bit.ly/Account4covidAF

An online conversation of frontline leaders ensuring accountability on COVID-19 Fund allocation in Africa. To join follow this link https://bit.ly/Account4covidAF

By Tundu AM Lissu.

Once again, we must bring unfortunate and regrettable news from Tanzania. We must, once more, ask the world to focus attention on the deteriorating human rights situation in my country.

On Monday July 29, Erick Kabendera, a well-known investigative journalist, who has worked for some of the major news organizations in this part of the world, was snatched from his home in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania’s commercial and economic hub. He was taken at gunpoint by heavily armed men, who had been brought to the area in unmarked cars and without any identification. Yesterday the Dar es Salaam Regional Police chief confirmed that Mr. Kabendera was being held for questioning in an undisclosed location. There was no prior information nor charge or arrest warrant against him; and the regional police chief did not give any reason for holding the respected newsman.

For all intents and purposes, it appears that Mr. Kabendera was abducted, and is now being held illegally.

Mr. Kabendera has been associated with some of the major exposés of human rights abuses and political repression in Tanzania in recent years. His investigative pen, for example, exposed the theft of Zanzibar’s presidential and parliamentary elections in 2015. How the Magufuli regime, and its henchmen, must have hated this courageous and principled man.

But Erick Kabendera is not the only victim of President Magufuli’s reign of terror. He is, on the contrary, one of the many in an increasingly long list of opposition leaders and activists, journalists, bloggers, businessmen and civic and religious leaders who have been targeted because of their political opinions. In this past month alone, a close associate of Zitto Zuberi Kabwe, a prominent opposition leader and lawmaker, was also abducted from his Dar es Salaam home. He was later found dumped in Mombasa, Kenya.

What is more, two weeks ago, a personal assistant to Bernard Membe, Tanzania’s former minister of foreign affairs (who is currently embroiled in an increasingly acrimonious war of words with Magufuli’s faction within the ruling party) was also abducted and disappeared for a few days before being released unharmed after a public outcry.

These abuses committed by the Magufuli regime will only worsen if left unchecked. The crimes of this regime must not only be exposed and denounced — they must also be deterred and punished. It is therefore high time for drastic actions to be taken. Financial sanctions, travel bans and visa restrictions should be imposed against all senior officials in the intelligence and security apparatus, as well as the ruling party political establishment and their families. Ideally, these individuals would be prevented or restricted from traveling or moving money and other assets abroad. These brazen human rights abusers would be made to understand that their state-orchestrated violence and terror against innocent civilians and the political opposition will not go unnoticed nor go unpunished by the international community.

The time to act is now, before it is indeed too late.

Honorable Tundu Lissu is a Tanzanian Member of Parliament, as well as the Attorney General and Central Committee member for CHADEMA, and the Chief Whip of the Official Opposition in Tanzania’s Parliament. Hon. Lissu is a longtime activist for democracy and human rights in Tanzania, and a practicing attorney. Between 2016 and July 2017, he was repeatedly arrested, unjustly detained and charged in court with arbitrary crimes due to his criticism of the ruling government. In September 2017, Lissu was targeted in a failed assassination attempt, suffering 16 bullet wounds The attack remains unsolved and no suspects have been identified nor any arrests made.

This article first appeared on Vanguard Africa.

The International Consortium of Investigative Journalists has revealed a large scale investigation which reveals how multinational companies used Mauritius to avoid taxes in countries in Africa, Asia, the Middle East and the Americas.

Mauritius Leaks is an investigation into how one law firm on a small island off Africa’s east coast helped companies leach tax revenue from poor African, Arab and Asian nations.

Based on 200,000 files, Mauritius Leaks exposes a sophisticated system that diverts tax revenue from poor nations back to the coffers of Western corporations and African oligarchs.

Some of the key findings:

For the full report and revelations go to the ICIJ website

Post written by Elizabeth Stuart, executive director of the Pathways for Prosperity Commission on inclusive technology. Originally published here

One of many puzzles in development is that increasing spending on health and education doesn’t necessarily deliver expected results.

To turn this on its head: Madagascar, Bangladesh and South Africa all have similar child mortality rates, but South Africa spends 19 times more than Madagascar and 13 times more than Bangladesh on healthcare.

Indeed this apparent paradox is one of the reasons why so many countries rushed to be part of the World Bank’s Human Capital Project, as they sought answers to precisely this question.

The Pathways to Prosperity Commission’s latest report is in part an attempt to provide a way through this puzzle by asking: what can technology do (if anything) to improve effectiveness and efficiency in health and education?

And because we’re a commission on inclusive technology, we also looked at whether tech can increase equity of access and outcomes.

This is what we found: there are lots of sensible reasons to be deeply sceptical about technology in this area. History is littered with pilots that worked for a while, but weren’t sustainable, such as the One Laptop per Child initiative in Peru, which 15 months after it started, had no measurable effects on maths and reading scores, in part because teachers hadn’t been trained on how to incorporate the laptops into their teaching. And this isn’t limited to developing countries: there are also cautionary tales from the US.

In other words digital can’t be just seen as a simplistic fix to analogue problems.

But, where policy makers started with a proper understanding of problems that need to be resolved, and assessed delivery obstacles and constraints by analysing the whole system, rather than just asking why a tablet in a classroom is not delivering results, we found clear evidence that technology is already significantly boosting outcomes

In India, a study of a free after-school programme that introduced Mindspark, a digital personalised learning service, showed improvements in mathematics assessment scores of up to 38% in less than five months.

In Uganda, the web-based application MobileVRS has helped increase birth registration rates in the country from 28% to 70%, at the very low cost of $0.03 per registration – thus helping decision-makers track health outcomes and improve access to services. And mental health patients in Nigeria who received SMS reminders for their next appointment were twice as likely to attend as patients receiving standard paper-based reminders.

But – and this is where it gets even more exciting – we also found evidence to suggest that in the near future, digital technologies will offer the promise to transform not just results, but the entire system.

For example, careful and deliberate low-cost data collection will make it possible for health and education systems, supported by digital technologies and artificial intelligence, to continuously learn and improve both standard practice and decision-making by creating feedback loops at every level. Projects such as BID (Better Immunization Data) in Zambia and Tanzania give us a glimpse of how, with the right tools and training, frontline providers can use data to improve their work.

By capturing and processing large volumes of individual data, technology will make personalised diagnosis and intervention possible in both health and education. It takes skill, training and time for a doctor to develop a personalised treatment plan or a teacher to personally coach a student, but algorithms can use test scores and patient records to design and implement individual plans at little cost.

Systems could also become more proactive to ensure services get to the people that need them most. In the health sector, this is starting to emerge in programmes that use community data to identify high-risk patients for active outreach. In education, it will allow more precise targeting of pupils whose learning is lagging.

Source: World Bank (2019d), Gapminder (2019), Pathways Commission analysis. Note: This figure uses data from 2013. Expenditure is adjusted for purchasing power parity, and is reported as 2011 international dollars. The size of a circle represents a country’s population.

Source: World Bank (2019d), Gapminder (2019), Pathways Commission analysis. Note: This figure uses data from 2013. Expenditure is adjusted for purchasing power parity, and is reported as 2011 international dollars. The size of a circle represents a country’s population.

And digital technologies also offer the means to explicitly focus on those who are left behind by current service delivery models. In Mali, a proactive community case management programme initiated by the NGO Muso contributed to a remarkable 10-fold decline in child mortality; the success of free door step health care is amplified with a dashboard and devices for community health workers. In Uganda, a portable ultrasound device, called Butterfly iQ allows healthcare workers to use their mobile phone as a scanner, anytime and anywhere.

But these visions will not come to fruition automatically. For most, the right digital infrastructure will need to be in place. This means access to electricity and the internet and digital skills, as well as clear rules for data governance and privacy will be essential. New regulations, protocols and rules will need to be established to guard against privacy violations, data misuse and algorithmic bias. And most importantly, even the most effective system will not frontload outcomes for the poorest if there is no deliberate effort to do so.

Urging caution on deployment is perhaps counterintuitive for a tech commission, but having seen many of the quick fix mistakes of the past we know for sure what doesn’t work. But what we also know is that, done right, and delivered at scale, technologically-enhanced health and education systems and the right digital connectivity, could unlock benefits that could be genuinely distributed to all – and that would be revolutionary.

This article was originally published on the From Poverty to Power blog

Recently, Cape Town in South Africa hosted one of its biggest events of the year: The Mining Indaba.

With two heads of state, 35 government ministers, and the world’s biggest mining companies attending thousands of meetings, and securing millions of dollars’ worth of deals — this conference remains the leading deal-making forum for the mining sector.

A couple of kilometres to the east, the industrial suburb of Woodstock hosted the Alternative Mining Indaba: a considerably less flashy congregation of community groups, church groups, and non-government organisations — including, of course, us, Transparency International (TI).

(Actually, our team worked around the clock attending both conferences and various side-events around South Africa’s beachfront city.)

So why is TI interested in this multi-billion dollar global industry?

It will come as no surprise to most people that corruption affects the extractive industries.

Where there’s smoke there’s fire — or in this case, where there’s money, lurks the risk of corrupt individuals abusing their entrusted power for private gain.

Remarkably, a quarter of all corruption cases in the oil, gas and mining sectors arise at the very start of those extractive projects?

This startling fact motivates us — a network of 20 TI chapters working in some of the world’s most resource-rich countries — to take a closer look at the very start of the mining value-chain: the awarding of mining licences, permits and contracts. If we can improve the system and ensure mining projects are developed on clean, accountable and transparent foundations, then the rest of the mining project is more likely to be corruption-free.

We need to tackle corruption in mining because when corruption compromises an industry as large, impactful and capital-intensive as the extractive industries, everyone loses.

People stand to lose their share of their nation’s mineral wealth, the cohesion of their communities and the health of their environments. Governments stand to lose important sources of revenue for public services such as schools or hospitals, and politicians risk losing the trust and confidence of citizens. Companies also stand to lose the business certainty and community support they need to secure their operations.

TI is working across our 20 country-strong network to shine a light on the often complex and obscure processes governing how mining licenses are granted. We are building coalitions against corruption across government, industry, civil society and community groups; and we are strengthening bonds across our anti-corruption networks to share information, tools and contacts.

This is a type of corruption that is not often spoken about but has serious impacts on human rights.

“Communities should feel and be part of the transformation,” says Farai Mutondoro, senior researcher for TI Zimbabwe, “in an ideal scenario, their voice is felt, their voice is heard by mining companies […] they have a say in terms of corporate social responsibility and the kind of infrastructure that they want to see.”

A key part of our work involves working with communities to enhance their access to information about mining projects, and to support them to know their rights and have their voices heard. Without transparency or access to this kind of information, communities cannot meaningfully participate in decisions that affect them. Worse still, they can be manipulated and taken advantage of. This is a type of corruption that is not often spoken about but has serious impacts on human rights.

“Transparency is so important to tackle corruption because transparency builds trust,” says Farai, “it ensures there is a social contract between communities and government.” Communities can then hold governments to account “because they have access to information that allows them to do so.”

Nicole Bieske, head of TI’s Mining Programme, found similar sentiments expressed at the Mining Indaba — “mining companies and politicians are reflecting more and more on how to build better relationships with the communities affected by mining operations.”

Nicole spoke at the Mining Indaba about the business imperative for building strong relationships with the communities living near mining projects. Community support matters, and companies must act responsibly if they are to build that trust.

“The great thing about TI’s work is that we are talking to everyone. And business is eager to learn more about how to improve business integrity, governments are listening to ideas to improve accountability, and people want more information about how mining licenses are granted on their land.”

This article was first published here

To learn more about TI’s work to improve transparency in mining, visit our website here.

This year’s Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI) presents a largely gloomy picture for Africa – only eight of 49 countries score more than 43 out of 100 on the index. Despite commitments from African leaders in declaring 2018 as the African Year of Anti-Corruption, this has yet to translate into concrete progress.

Seychelles scores 66 out of 100, to put it at the top of the region. Seychelles is followed by Botswana and Cabo Verde, with scores of 61 and 57 respectively. At the very bottom of the index for the seventh year in a row, Somalia scores 10 points, followed by South Sudan (13) to round out the lowest scores in the region.

With an average score of just 32, Sub-Saharan Africa is the lowest scoring region on the index, followed closely by Eastern Europe and Central Asia, with an average score of 35.

Sub-Saharan Africa remains a region of stark political and socio-economic contrasts and many longstanding challenges. While a large number of countries have adopted democratic principles of governance, several are still governed by authoritarian and semi-authoritarian leaders. Autocratic regimes, civil strife, weak institutions and unresponsive political systems continue to undermine anti-corruption efforts.

Countries like Seychelles and Botswana, which score higher on the CPI than other countries in the region, have a few attributes in common. Both have relatively well-functioning democratic and governance systems, which help contribute to their scores. However, these countries are the exception rather than the norm in a region where most democratic principles are at risk and corruption is high.

Notwithstanding Sub-Saharan Africa’s overall poor performance, there are a few countries that push back against corruption, and with notable progress.

Two countries – Côte d’Ivoire and Senegal – are, for the second year in a row, among the significant improvers on the CPI. In the last six years, Côte d’Ivoire moved from 27 points in 2013 to 35 points in 2018, while Senegal moved from 36 points in 2012 to 45 points in 2018. These gains may be attributed to the positive consequences of legal, policy and institutional reforms undertaken in both countries as well as political will in the fight against corruption demonstrated by their respective leaders.

With a score of 37, Gambia improved seven points since last year, while Seychelles improved six points, with a score of 66. Eritrea also gained four points, scoring 24 in 2018. In Gambia and Eritrea, political commitment combined with laws, institutions and implementation help with controlling corruption.

In the last few years, several countries experienced sharp declines in their CPI scores, including Burundi, Congo, Mozambique, Liberia and Ghana.

In the last seven years, Mozambique dropped 8 points, moving from 31 in 2012 to 23 in 2018. An increase in abductions and attacks on political analysts and investigative journalists creates a culture of fear, which is detrimental to fighting corruption.

Home to one of Africa’s biggest corruption scandals, Mozambique recently faced indictments of several of its former government officials by US officials. Former finance minister and Credit Suisse banker, Manuel Chang, is charged with concealing more than US$2 billion dollars of hidden loans and bribes.

Many low performing countries have several commonalties, including few political rights, limited press freedoms and a weak rule of law. In these countries, laws often go unenforced and institutions are poorly resourced with little ability to handle corruption complaints. In addition, internal conflict and unstable governance structures contribute to high rates of corruption.

Angola, Nigeria, Botswana, South Africa and Kenya are all important countries to watch, given some promising political developments. The real test will be whether these new administrations will follow through on their anti-corruption commitments moving forward.

With a score of 27, Nigeria remained unchanged on the CPI since 2017. Corruption was one of the biggest topics leading up to the 2015 election and it is expected to remain high on the agenda as the country prepares for this year’s presidential election taking place in February.

Nigeria’s Buhari administration took a number of positive steps in the past three years, including the establishment of a presidential advisory committee against corruption, the improvement of the anti-corruption legal and policy framework in areas like public procurement and asset declaration, and the development of a national anti-corruption strategy, among others. However, these efforts have clearly not yielded the desired results. At least, not yet.

With a score of 19, Angola increased four points since 2015. President Joao Lourenco has been championing reforms and tackling corruption since he took office in 2017, firing over 60 government officials, including Isabel Dos Santos, the daughter of his predecessor, Eduardo Dos Santos. Recently, the former president’s son, Jose Filomeno dos Santos, was charged with making a fraudulent US$500 million transaction from Angola’s sovereign wealth fund. However, the problem of corruption in Angolan goes far beyond the dos Santos family. It is very important that the current leadership shows consistency in the fight against corruption in Angola.

With a score of 43, South Africa remains unchanged on the CPI since 2017. Under President Ramaphosa, the administration has taken additional steps to address anti-corruption on a national level, including through the work of the Anti-Corruption Inter-Ministerial Committee. Although the National Anti-Corruption Strategy (NACS) has been in place for years, the current government continues to build momentum for the strategy by soliciting public input.

In addition, citizen engagement on social media and various commissions of inquiry into corruption abuses are positive steps in South Africa. The first commission of inquiry, the Zondo Commission, focuses on state capture, while the second focuses on tax administration and governance of the South African Revenue Service (SARS). Given that previous commissions of inquiry produced few results, the jury is still out on whether the new administration will yield more positive change.

Another example of recent anti-corruption efforts in South Africa is the Special Investigating Unit (SIU) report on corruption in the Gauteng Department of Health. While the report never saw the light of day under previous administrations, under President Ramaphosa it exposed several high profile individuals, including members of the ruling party.

In both Kenya and South Africa, citizen engagement in the fight against corruption is crucial. For example, social media has played a big role in driving public conversation around corruption. The rise of mobile technology means ordinary citizens in many countries now have instant access to information, and an ability to voice their opinions in a way that previous generations did not.

In addition to improved access to information, which is critical to the fight against corruption, government officials in Kenya and South Africa are also reaching to social media to engage with the public. Corruption Watch, our chapter in South Africa, has seen a rise in the number of people reporting corruption on Facebook and WhatsApp. However, it remains to be seen whether social media and other new technologies will spur those in power into action.

Governments in Sub-Saharan Africa must intensify their efforts and keep in mind the following issues, when tackling corruption in their countries:

This article was originally published on the Transparency International website

Exploring what it takes to enhance social accountability practice.

The conference theme aims to interrogate the challenges of working in the social accountability field and specifically the elements which allow for successful social accountability practice, where practitioners are able to enhance the interaction between the state and the public. The conference will explore the manner in which social accountability practice is impacted by context, by power, by the ecosystem of actors within the sector and by actors we may consider outside of the ecosystem.

Download the conference PROGRAMME

You can link to a livestream of the plenary presentations and panels on the 11th and 12th September here

An interview with Nathaniel Heller, Results for Development. Originally published here

By now, I think we can all agree that we’ve reached the peak of big data, returned to base camp, washed our kit and started planning the next climb. For a short while, big data was presented as the solution to all our problems. The premise was simple — collect more data, make it look pretty, push it out and people would start using it to make decisions that would end poverty, expose corruption and reverse unsustainable exploitation of our environment.

But things didn’t work out that way. In the rush to deliver data to the people, the people forgot the people. Bigger didn’t mean better and data dashboards became graveyards filled with withering flowers.

Data designed for the living need to be centered around humans and the unique needs we all have. Results for Development (R4D) is an organisation that puts the users of data at the centre of all their efforts to achieve sustainable progress in health, education and nutrition. I spoke to Nathaniel Heller, Executive Vice President for Integrated Strategies at R4D to learn more about their user-centric approach to data and the importance of thinking ‘small’ when it comes to helping people make better use of data.

“There’s a mistaken belief that if we present people with pretty data, good decisions will happen,” said Nathaniel. “But data isn’t the only input into decision-making. You have to consider the capacity of the governments or organisations involved to carry out the task they’ve been given and what hurdles they have to overcome. The use of data in decision-making is much more nuanced than simply making more data available.”

R4D works with change agents to find long-lasting solutions. Focusing on identifying important and transformational data, R4D will only invest in data tools if there’s a strong case for it. “Sometimes it seems like there’s a data problem,” explained Nathaniel, “but once you start talking to people about what they need, you’ll see there’s another underlying issue that has nothing to do with the data.” It’s these underlying issues that R4D’s user-centric approach to problem solving uncovers.

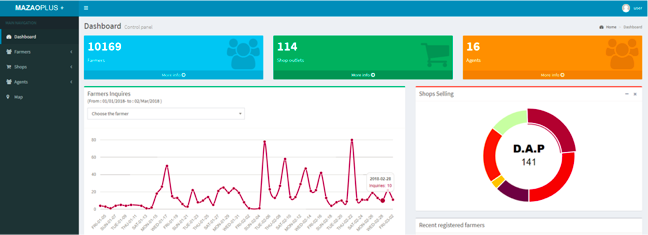

To illustrate his point, Nathaniel told me about a current project that he’s particularly excited about. R4D spent about year poring over all different kinds of country-level agricultural data in several African countries to identify opportunities for agricultural transformation — the kind of macro shift that has the potential to lift tens of millions out of poverty and address nutritional needs. The initial idea was to create a dashboard and open up access to the data, assuming this would motivate national political leaders to embrace a push for change. But when R4D spotted an opportunity in the data (only a tiny percentage of smallholder farmers in Kenya use inorganic fertilizer), they decided to shift strategies.

In Kenya, getting the right fertiliser can be an expensive and time consuming effort for farmers. A half-day journey to the market might end with the purchase of the wrong fertilizer, or worse, a counterfeit product that does more harm than good. R4D and their partners at the Local Development Research Institute saw an opportunity to create a service that would help people locate the right fertiliser, for the right price, from a location within easy travelling distance.

MazaoPlus+, an SMS service for farmers (and its accompanying Android app used by field agents to onboard users) was built in just two weeks. More than 10,000 farmers have already subscribed to receive fertiliser advice via their phones. We have to wait until harvest time to see if the app has helped improve yields through improved access to fertilizer, but Nathaniel sees a great potential in this service, both in terms of the agricultural impact and potential for scaling up into something bigger.

“The Kenyan fertiliser SMS service is a good example of our methods where we emphasise fit-for-purpose principles when it comes to leveraging data; we often focus on the small data, not the big data,” said Nathaniel. “We thought it through first and built second; which is exactly how every project should go.”

Small data is a term that’s never been as popular as big data but it describes data that are presented in a volume and format that’s easy for humans to access and use. Whereas reams of big data can be collected and processed by artificial intelligence, small data is curated by humans for other humans. The personal touch of small data ensures the solutions being developed to improve education, healthcare and agricultural systems are meeting a real need and supporting change.

On their website, R4D speaks about “artificial solutions”, whereby resource-constrained governments find themselves forced to adopt data-for-development tools without adequate planning or data uptake strategies. I asked Nathaniel how these artificial solutions could be avoided. “When someone proposes a solution, you start by asking, ‘has anyone (other than the funder) asked for this?’” said Nathaniel. “If they say yes, good, but if not you need to dig deeper and ask more questions. Structured interviews with potential users provides lots of interesting feedback that will help you understand their needs and pain points, enabling you to determine if the root cause of their problems really is a data issue, or something else entirely.”

Talking and listening to your users to learn what they need is common sense but it’s always worth reminding ourselves why. As Nathaniel and R4D have shown, understanding the needs of people and developing a solution that’s tailored to them will always be more effective than taking a ‘store-bought’ solution and moulding it to their situation. After all, one-size-fits-all rarely fits anyone. When — and only when — data is identified as the true issue, every care must be taken to curate it and package it in ways that are accessible, usable and useful for the users. These are principles Vizzuality shares with R4D, so let’s think small when it comes to big data.

In celebration of International Right to Information Day in 2015, the African Platform on Access to Information (APAI) Campaign and fesmedia Africa released a research study on the state of access to information in Africa. The research provides a useful snapshot of the state of access to information on the continent while providing clear and simple summaries and infographics, measured against the APAI Declaration of Principles.

The study examines Cote D’Ivoire, Kenya, Madagascar, Malawi, Mozambique, Namibia, Niger, Nigeria, South Africa, Tanzania, Uganda, and Zimbabwe.

The results across the countries examined revealed that the existence of an ATI law is a necessary, but insufficient, step for ensuring a positive access to information environment. Problems with the implementation of ATI laws often cited a lack of awareness of the laws, and weak political will for implementation, as key inhibitors. Both of these factors highlight the important role ATI activists must play in developing the positive discourse around ATI to both encourage users, as well as bureaucratic and administrative actors.

You can download the full report STATE OF ACCESS TO INFORMATION IN AFRICA 2017