Recently, Cape Town in South Africa hosted one of its biggest events of the year: The Mining Indaba.

With two heads of state, 35 government ministers, and the world’s biggest mining companies attending thousands of meetings, and securing millions of dollars’ worth of deals — this conference remains the leading deal-making forum for the mining sector.

A couple of kilometres to the east, the industrial suburb of Woodstock hosted the Alternative Mining Indaba: a considerably less flashy congregation of community groups, church groups, and non-government organisations — including, of course, us, Transparency International (TI).

(Actually, our team worked around the clock attending both conferences and various side-events around South Africa’s beachfront city.)

So why is TI interested in this multi-billion dollar global industry?

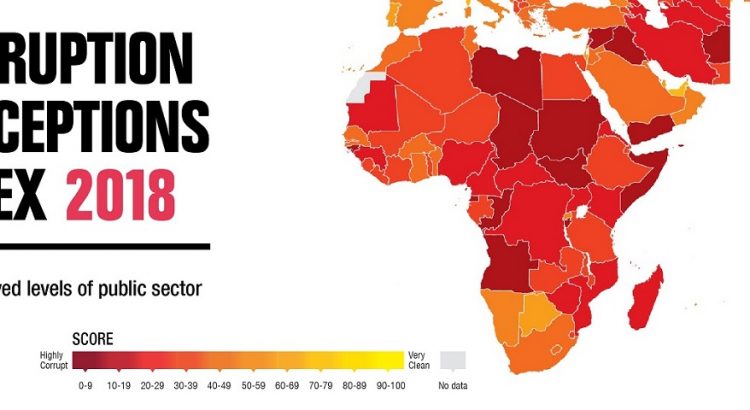

It will come as no surprise to most people that corruption affects the extractive industries.

Where there’s smoke there’s fire — or in this case, where there’s money, lurks the risk of corrupt individuals abusing their entrusted power for private gain.

Remarkably, a quarter of all corruption cases in the oil, gas and mining sectors arise at the very start of those extractive projects?

This startling fact motivates us — a network of 20 TI chapters working in some of the world’s most resource-rich countries — to take a closer look at the very start of the mining value-chain: the awarding of mining licences, permits and contracts. If we can improve the system and ensure mining projects are developed on clean, accountable and transparent foundations, then the rest of the mining project is more likely to be corruption-free.

We need to tackle corruption in mining because when corruption compromises an industry as large, impactful and capital-intensive as the extractive industries, everyone loses.

People stand to lose their share of their nation’s mineral wealth, the cohesion of their communities and the health of their environments. Governments stand to lose important sources of revenue for public services such as schools or hospitals, and politicians risk losing the trust and confidence of citizens. Companies also stand to lose the business certainty and community support they need to secure their operations.

TI is working across our 20 country-strong network to shine a light on the often complex and obscure processes governing how mining licenses are granted. We are building coalitions against corruption across government, industry, civil society and community groups; and we are strengthening bonds across our anti-corruption networks to share information, tools and contacts.

This is a type of corruption that is not often spoken about but has serious impacts on human rights.

“Communities should feel and be part of the transformation,” says Farai Mutondoro, senior researcher for TI Zimbabwe, “in an ideal scenario, their voice is felt, their voice is heard by mining companies […] they have a say in terms of corporate social responsibility and the kind of infrastructure that they want to see.”

A key part of our work involves working with communities to enhance their access to information about mining projects, and to support them to know their rights and have their voices heard. Without transparency or access to this kind of information, communities cannot meaningfully participate in decisions that affect them. Worse still, they can be manipulated and taken advantage of. This is a type of corruption that is not often spoken about but has serious impacts on human rights.

“Transparency is so important to tackle corruption because transparency builds trust,” says Farai, “it ensures there is a social contract between communities and government.” Communities can then hold governments to account “because they have access to information that allows them to do so.”

Nicole Bieske, head of TI’s Mining Programme, found similar sentiments expressed at the Mining Indaba — “mining companies and politicians are reflecting more and more on how to build better relationships with the communities affected by mining operations.”

Nicole spoke at the Mining Indaba about the business imperative for building strong relationships with the communities living near mining projects. Community support matters, and companies must act responsibly if they are to build that trust.

“The great thing about TI’s work is that we are talking to everyone. And business is eager to learn more about how to improve business integrity, governments are listening to ideas to improve accountability, and people want more information about how mining licenses are granted on their land.”

This article was first published here

To learn more about TI’s work to improve transparency in mining, visit our website here.