The 2018 Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI) released in January 2018 by Transparency International reveals that the continued failure of most countries to significantly control corruption is contributing to a crisis of democracy around the world. “With many democratic institutions under threat across the globe – often by leaders with authoritarian or populist tendencies – we need to do more to strengthen checks and balances and protect citizens’ rights,” said Patricia Moreira, Managing Director of Transparency International.

“Corruption chips away at democracy to produce a vicious cycle, where corruption undermines democratic institutions and, in turn, weak institutions are less able to control corruption.”

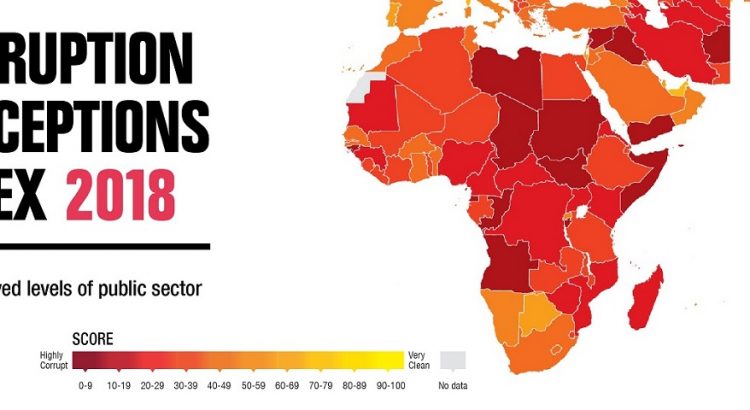

The 2018 CPI draws on 13 surveys and expert assessments to measure public sector corruption in 180 countries and territories, giving each a score from zero (highly corrupt) to 100 (very clean). To view the results, visit: www.transparency.org/cpi2018

CPI highlights

More than two-thirds of countries score below 50, with an average score of only 43. Since 2012, only 20 countries have significantly improved their scores, including Estonia and Côte D’Ivoire, and 16 have significantly declined, including, Australia, Chile and Malta.

Denmark and New Zealand top the Index with 88 and 87 points, respectively. Somalia, South Sudan, and Syria are at the bottom of the index, with 10, 13 and 13 points, respectively. The highest scoring region is Western Europe and the European Union, with an average score of 66, while the lowest scoring regions are Sub-Saharan Africa (average score 32) and Eastern Europe and Central Asia (average score 35).

Corruption and the crisis of democracy

Cross analysis with global democracy data reveals a link between corruption and the health of democracies. Full democracies score an average of 75 on the CPI; flawed democracies score an average of 49; hybrid regimes – which show elements of autocratic tendencies – score 35; autocratic regimes perform worst, with an average score of just 30 on the CPI. Exemplifying this trend, the CPI scores for Hungary and Turkey decreased by eight and nine points respectively over the last five years. At the same time, Turkey was downgraded from ‘partly free’ to

‘not free’, while Hungary registered its lowest score for political rights since the fall of communism in 1989. These ratings reflect the deterioration of rule of law and democratic institutions, as well as a rapidly shrinking space for civil society and independent media, in those countries.

More generally, countries with high levels of corruption can be dangerous places for political opponents. Practically all of the countries where political killings are ordered or condoned by the government are rated as highly corrupt on the CPI.

Countries to watch

With a score of 71, the United States lost four points since last year, dropping out of the top 20 countries on the CPI for the first time since 2011. The low score comes at a time when the US is experiencing threats to its system of checks and balances as well as an erosion of ethical norms at the highest levels of power. Brazil dropped two points since last year to 35, also earning its lowest CPI score in seven years.

Alongside promises to end corruption, the country’s new president has made it clear that he will rule with a strong hand, threatening many of the democratic milestones achieved by the country. “Our research makes a clear link between having a healthy democracy and successfully fighting public sector corruption,” said Delia Ferreira Rubio, Chair of Transparency International. “Corruption is much more likely to flourish where democratic foundations are weak and, as we have seen in many countries, where undemocratic and populist politicians can use it to their advantage.”

To make real progress against corruption and strengthen democracy around the world, Transparency International calls on all governments to:

• strengthen the institutions responsible for maintaining checks and balances over political power, and ensure their ability to operate without intimidation;

• close the implementation gap between anti-corruption legislation, practice and enforcement;

• support civil society organisations which enhance political engagement and public oversight over government spending, particularly at the local level;

• support a free and independent media, and ensure the safety of journalists and their ability to work without intimidation or harassment.