Silas Okumu leads the parent teacher association at a primary school in Kisenge, a small community just 600 meters from Uganda’s border with the Democratic Republic of Congo. In October 2018, he travelled six hours by bus to the capital, Kampala, to talk to the Africa Freedom of Information Centre (AFIC), a non-profit that works on contract monitoring, about a construction project at the school where his four children are students.

Recounting the details from neat handwritten papers, he explained that new classrooms and an administrative block had been built (with support from the Global Partnership for Education and the World Bank), but the community had unresolved concerns: there weren’t enough classrooms for all the students, the school lacked teachers’ housing, a fence and electricity, and the new classrooms weren’t furnished.

AFIC’s staff had visited Kisenge primary school when construction was underway, checking the quality of building materials and following up when things weren’t going well with the contractors. When Okumu told them about the community’s other requests, they advised him to write the details down and promised to inform the relevant authorities. Okumu had come to Kampala to deliver his letter in person, so AFIC could share it with various government offices and follow up to ensure action was taken.

Demanding accountability: a network tracking public contracting across Uganda

AFIC is part of a network of passionate Ugandans who dedicate their time to tracking public contracting processes across the country, helping citizens like Silas Okumu to ensure their communities get the goods, services and works they need, and public officers have the information and resources they need to purchase those items at the fairest price. The group is diverse, but shares a common goal: “value for money, value for many.” They believe this occurs most effectively when people understand the contracts that affect their communities and participate in decisions made about those deals — from companies wanting to do business with the government to citizens who benefit from the services.

Before open contracting was established, citizens made complaints and requests about contracts on an ad-hoc basis, they didn’t know whether any action was taken, and there was often little clarity about which government office was responsible for what processes.

The strength and collaborative nature of this group has helped them to advocate successfully for the government to adopt open contracting — a best practice approach designed to improve the management and performance of public contracting through open data and public engagement. It’s an ambitious project — corruption is endemic in Uganda, especially in public procurement, the anti-graft laws are poorly enforced, freedom of speech is often restricted, and government agencies are under-resourced. Unreliable IT infrastructure and technology make setting up stable digital resources a challenge.

But there are early signs this network’s efforts seem to begin paying off. The government has used open contracting to begin making its public procurement portal more useful for a wider range of people. Civil society has created their own platform that displays procurement information in a way that’s easy for community monitors to understand, drawing on open data extracted from the government’s portal and supplemented by FOI requests. The public procurement agency is using open contracting data to identify potential irregularities in procurement processes. Public access to contracting documents has improved since open contracting reforms were introduced, as have communication channels between citizens, civil society and public servants. Meanwhile, the government is drafting an amendment to the procurement law, the PPDA Act, that would improve transparency and accountability in the sector. There have also been notable improvements reported in some procurement policies and practices; in particular, public officers say contracting data has helped them to plan and budget better, and open contracting has been embedded in anti-corruption reforms within the country’s largest procuring entity.

Towards a new, more collaborative and open approach to public contracting

AFIC’s executive director Gilbert Sendugwa recalls reporting anomalies to the national procurement oversight body, the Public Procurement and Disposal of Public Assets Authority (PPDA), as early as 2011, when he was the chairman of a board of governors overseeing education development projects in Rushenyi county. He says the PPDA didn’t respond to him directly, but speaking to beneficiaries sometimes revealed that complaints had been addressed.He continued to share information with the PPDA informally, before they signed a formal agreement with him. When a coalition of procurement monitors was established, PPDA began hosting their meetings and training them on the agency’s processes. Now “we work very warmly and very openly in a strong partnership,” Sendugwa says

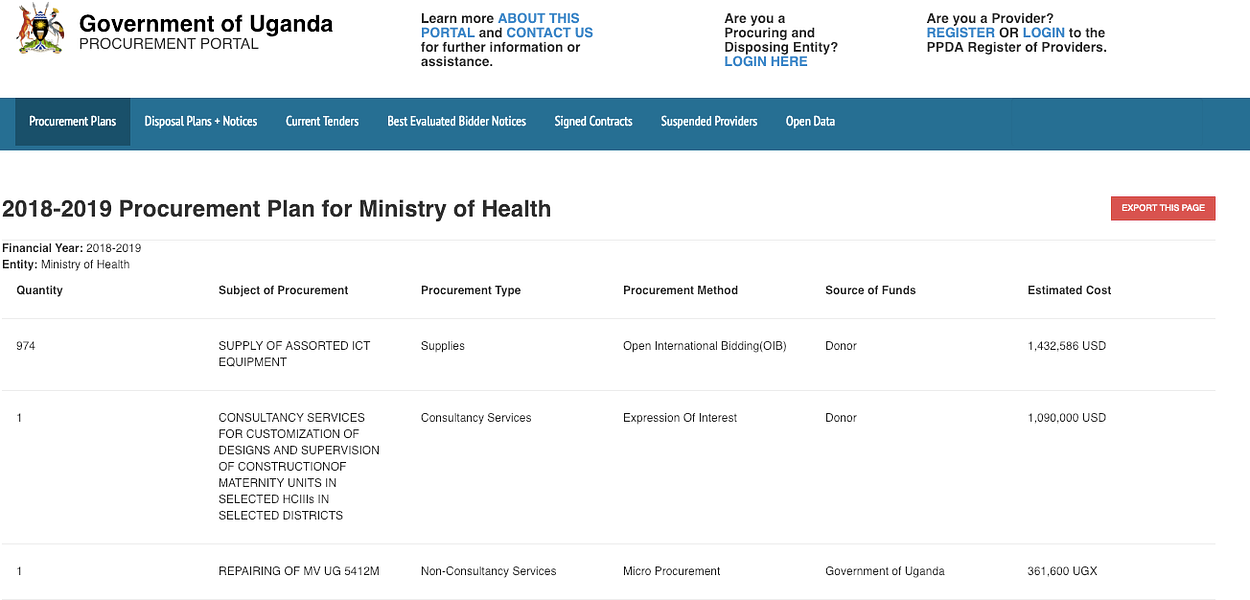

In 2015, the PPDA launched the Government Procurement Portal (GPP), an online platform to systematically publish contracting information. But despite its good intentions, civil society groups found it difficult to use. The platform featured data on procurement plans, tender notices, winning bidders’ names, awards, contract status and suspended suppliers. But many procuring entities didn’t publish their data, and contracting processes lacked unique identifiers so they couldn’t be followed through different stages of the procurement cycle. Important data were also missing — such as detailed bidder information, award criteria, implementation milestones and amendments, and procurement plans for local district governments (see detailed data mapping) — and the data formats weren’t user-friendly.

AFIC began advocating for open contracting with the Uganda Contracts Monitoring Coalition (UCMC) five years ago, as a way to make information about contracts more accessible, useful and timely. With the help of fellow transparency advocates from Nigeria and elsewhere, AFIC used open contracting mapping tools to assess the quality of the procurement agency’s data against international standards, and how the GPP could be improved to allow better monitoring by civil society. In 2016, they compared a sample of GPP data against the Open Contracting Data Standard (OCDS), a universal schema for organizing the most important information about contracting processes, from the planning stage to award and implementation.

The OCDS made gaps in the data apparent, such as planning and implementation milestones, bidder enquiries, and tender updates. After hearing AFIC’s findings and recommendations, the procurement agency asked the civil society group to expand their assessment to cover all the portal’s data and agreed to redesign the portal in line with the OCDS. The PPDA was convinced because they could see the benefit of open contracting to their work — improving disclosure, public participation, and public sector responsiveness would improve their capacity to monitor public procurement, and create better practices among procuring entities, who often had a reputation for failing to follow procurement rules, in some cases awarding contracts based on personal or political preferences rather than value for money. Now, PPDA data shows 402 procuring entities are registered on the GPP, 202 of which disclosed procurement plans for the 2017/18 fiscal year, compared to 97 entities registered in 2015/16 before the redesign. Each contracting process has a unique identifier across the procurement cycle and data is in accessible and reusable formats (Excel and JSON).

Edwin Muhumuza, performance monitoring manager at the PPDA shares: “… for citizens to be engaged in promoting accountability for effective service delivery, they must have information related to the contracts that are being implemented in their localities. Our commitment to open contracting is also intended to leverage the capabilities of other stakeholders such as civil society organizations in monitoring public contracts. Making public procurement information accessible to the public also enables us to take advantage of the civil society organizations’ networks that can supplement and complement our efforts in contract monitoring. We have seen the fruits of such collaboration, and they have encouraged us to promote open contracting.”

Putting open contracting data to use: Identifying red flags

With open data, the PPDA has enough complete records to flag and investigate anomalies, such as incorrect award methods, overpricing, and time overruns. For example, an officer at the PPDA noticed that the bid process was restricted for a valuable contract for supervisory services at the Kabaale International Airport. Normally Uganda would run an open competitive procedure for a 21.3 billion shilling (US$5.7 million) contract, according to Edwin Muhumuza. But after making further enquiries, Muhumuza told us, the PPDA found the direct award was legal, because it was requested by the international funder and international agreements take precedence over other procurement legislation (the PPDA Act).

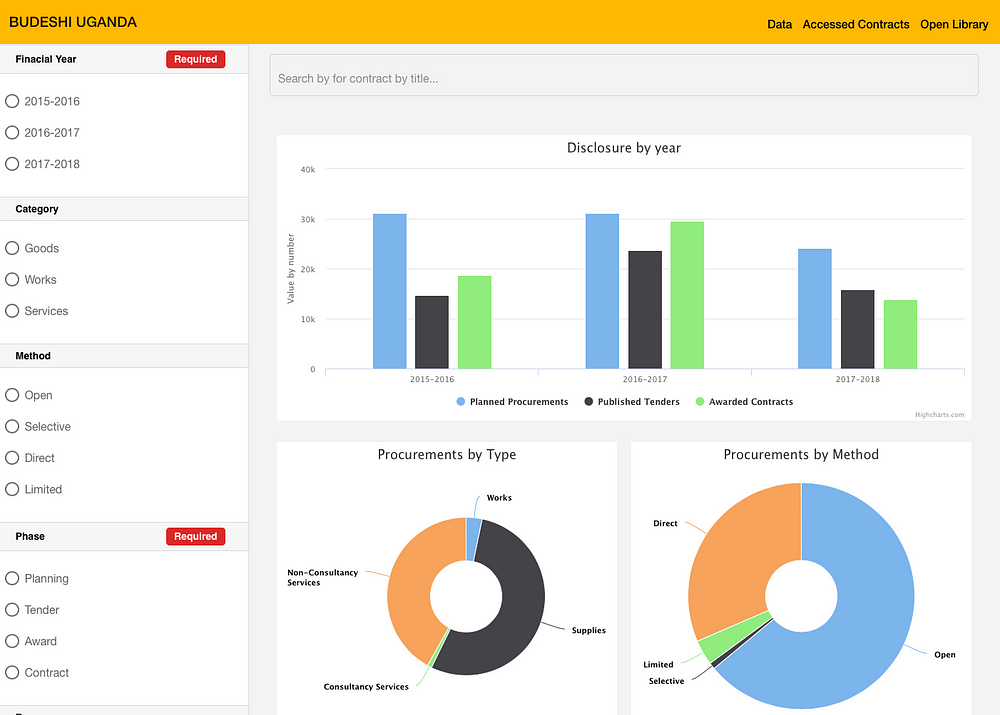

AFIC has extracted data from the GPP to build their own tool specifically designed for civil society and citizens, Budeshi.ug, which it released in October 2018. The GPP data in Budeshi is further supplemented by contracts and information obtained through Freedom of Information requests. The tool is an adaptation of one developed by AFIC’s partners in Nigeria, the Public and Private Development Centre (PPDC). Like the Nigerian platform, Budeshi.ug offers powerful analyses focused on information of interest to citizens and civil society in particular. It allows users to search projects by procuring entity, contractor, procurement method, project type, and year, and run basic analyses on the aggregated data. AFIC also plans to upload other data sets, such as budget and spending data, to perform further analysis. This cross-referencing of data sets can lead to powerful insights. For example, Emanuele Colonnelli, an academic and researcher collaborating with the PPDA, said he requested Uganda’s tax registry data manually and combined it with GPP data to reveal 45% of firms doing business with government never pay taxes (study yet to be published).

A shared mission for better procurement: building relationships between civil society and government

Members of civil society from AFIC and UCMC have repeated their evidence-based advocacy approach to earn the trust of other institutions who had been unresponsive, even when the civil society groups invoked access to information laws. Their monitoring work serves several purposes: to increase communities’ understanding of individual projects — looking for signs of common problems like potential fraud, collusion, diversion of funds, or inflated costs — and to motivate government agencies to engage more actively in open contracting, which in turn increases the amount and quality of data on the GPP.

Through this work, we have seen that proactive disclosure and collaboration have improved among district governments where civil society monitors contracts and the PPDA has trained procurement officers in using and uploading data to the portal.

Before their first monitoring report was finalized, AFIC shared their draft findings and recommendations with the relevant agencies and incorporated their input in the final report. They invited elected officials who have an oversight role, accounting officers and the heads of departments. This helped to improve accountability, but it also gave different stakeholders a chance to raise concerns about capacity or resource needs.

“Initially in these districts they were not cooperating, giving us information and contracts,” said Sendugwa. “We had to get some of them through the PPDA. But after our first report, when we shared results, that’s when it opened doors to establish formal relationships.”

Shortly after, three districts signed MoUs with AFIC to share their contracting information. Six months later, when AFIC conducted their second round of monitoring, they gathered more than three times as many contracts (98 contracts, 37 of which were accessed via the GPP, compared to 29 contracts in 2017, all accessed via FOI request) and all five districts’ procurement plans (three via the GPP). The other two districts signed MoUs after the second monitoring period. After this improvement in data disclosure, PPDA registered 43 additional procuring entities to the GPP and trained 86 officers from these entities on using the open contracting data portal.

The PPDA and Ministry of Finance also adopted AFIC’s recommendation to enshrine open contracting in the procurement legislation. An amendment to the PPDA Act is currently being drafted by the First Parliamentary Counsel.

At the agency level, open contracting has been embedded in important measures to address endemic corruption in the largest procuring entity, Uganda National Roads Authority (UNRA) (a commission of inquiry in 2016, for example, found the agency had misappropriated more than 40% of its road construction budget over seven years). According to the PPDA, the entity has begun publishing additional procurement information, such as procurement plans, via digital platforms and traditional media, and engaging more with contractors and other stakeholders. This has helped potential bidders to plan better and make more competitive offers, according to the UNRA’s Procurement Director John Omeke Ongimu. Several people interviewed from government and civil society also said bids per tender at the UNRA have increased and come from a wider range of firms and countries. Reported improvements like these represent an encouraging first step in the right direction, and the Open Contracting Partnership (OCP) hopes to conduct a quantitative evaluation of them in the near future.

Better planning and budgeting

Officers from central government agencies and district governments told the OCP that compliance has improved and procurement processes are more efficient and transparent since the GPP was updated. For example, timelines and automated notifications of delays help them to track processes; the list of blacklisted suppliers helps them evaluate proposals; and bid notices can be printed by providers, rather than collected in person after being prepared manually.

Procurement plans have become more realistic and within budget, according to the government officials interviewed. A procurement officer at the Ministry of Education, Richard Ahimbisibwe, said the ministry’s budgeting has improved, because they and the PPDA can monitor actual spending against procurement plans more efficiently. When the ministry’s initial procurement plan for the 2017/18 fiscal year was over budget by 200 billion shillings, the PPDA followed up with the procurement unit, who took a second look and found they were able to remove some unnecessary items and cut costs of others to bring the plan within budget.

Civil society has observed improvements in procurement planning, too. Only 21 percent of the contracts obtained by AFIC for their first monitoring reportin October 2017 were included in the government’s approved procurement plans (6 out of 29 contracts), which could indicate a diversion of funds. Their second report, in April 2018, revealed a significant improvement — 86 percent of contracts were in the plans (32 out of 37 contracts analyzed). AFIC has added information on the contracts obtained via FOI request to the Budeshi monitoring platform.

Between the two monitoring periods, PPDA trained procurement officers in the districts and updated the planning template in the GPP to ensure a link between planned contracts and those being awarded and executed. Now, if a contract is not in the procurement plan, it cannot be entered in the GPP. And government has a better understanding of who in government buys what, from whom and when.

Next steps and embedding a change of culture

While the story so far shows the promise for open data and open contracting in Uganda’s public procurement, it’s also very volatile. The GPP was down for half of 2018 and a new e-procurement system is in development, which could derail some of the progress, as it’s unclear to what extent it will integrate open contracting and the work already invested in the GPP.

At the institutional level, major weaknesses in the enforcement of legislation and procurement processes continue to allow for corruption and impunity, according to representatives of both government and civil society.

“Government has made progress in disclosing contracting information,” said Sendugwa. “Several investigations and commissions of inquiry have been made in procurement-related scandals. However, these efforts are undermined by lack of action against the big fish when [they] are involved in corrupt practices.”

The PPDA’s Executive Director Benson Turamye has expressed similar concerns, noting in a statement for Uganda’s 2017 Anti-Corruption Week that despite procurement reforms having some success, “serious challenges persist including corruption, non-compliance with the procurement act and regulations, un-standardized procurement processes across procuring and disposal entities, continuous delays in delivery of supplies and services, and wastage of resources through uncompetitive and closed purchases.” He also mentioned a 2015 PPDA survey that found almost 60 percent of bidders said they had paid a public official to influence the outcome of a tender.

Uganda is working now on redesigning the GPP so that it can hold large amounts of data and remain stable. But where we really need the investment, according to Gilbert Sendugwa, is in promoting use of data by different stakeholders.

“[We want] those who are mandated for oversight to be able to use this data to empower their decision making, [along with] those who are involved in service monitoring…and those who implement contracts,” says Gilbert Sendugwa.

Citizens particularly need more information about what happens to the complaints made, as they develop more confidence in requesting contracting documents and dealing with officials.

The persistence of Silas Okumu, who had been calling AFIC every day, is paying off for Kisenge primary school. Staff absenteeism was a problem because teachers lived far away, so the community asked to repurpose iron sheets from the school’s construction site to build teacher housing. AFIC informed the Ministry of Education who decided that iron sheets at all similar World Bank project sites should be given to the communities for teacher housing. Unaware that the community knew about this decision, contractors started removing iron sheets designated for Kisenge primary school staff accommodation. Okumu immediately called Gilbert Sendugwa, who contacted the district government. He asked them to stop the contractors since they had a letter from the Ministry of Education explaining that the materials were for the community. They didn’t cooperate, so Sendugwa called the local police commissioner. When the contractors continued to take the materials, Sendugwa told the commissioner that he was reporting the situation to the Inspectorate of Government and would inform them that the commissioner was following up to help. After about an hour after the call, Chairman Okumu said the iron sheets had been returned to the school.

“I found it very interesting, but also humbling — the power of information by the community,” said Sendugwa. Open contracting in Uganda is still a work in progress but thanks to the efforts of AFIC, the PPDC and committed local activists, the journey has begun.

This article was originally published by Open Contracting here

Additional resources:

Making public contracts work for people: Experiences from Uganda

Eyes on contracts: Citizens’ voice in improving the performance of public contracts in Uganda

Uganda open contracting and procurement data use scoping study report