Tolu Olarewaju, Staffordshire University

Corruption can have a crippling effect on a country’s economy. This is why African businesses have described ending corruption as “priority number one”.

Take Nigeria, where the basic infrastructure deficit is huge but funds to improve its infrastructure always seem to end up missing or misallocated. In addition, projects are started and never finished. As a result the country’s roads, rail and ports are in a deplorable state.

Nigerians also suffer from persistent electricity shortages. They lack pipe-borne water and proper sanitation facilities. Housing provision is a problem too.

The country has spent billions of US dollars to resuscitate its power and transport sectors. But it has very little to show for it. Nigeria is not alone. Researchers often report that infrastructure spending is regularly used by public officers and government officials across the continent to misappropriate funds.

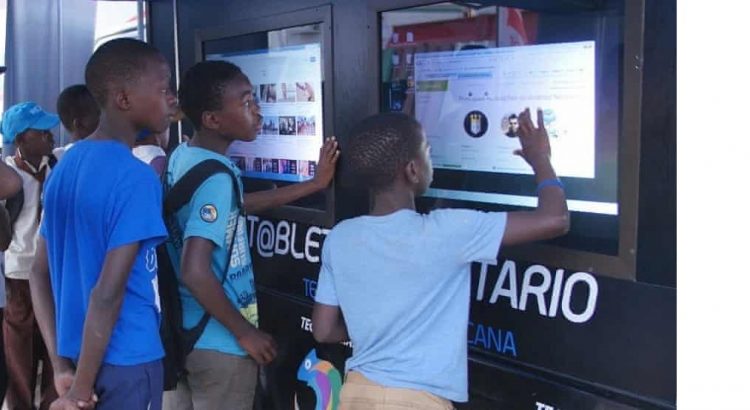

Tackling corruption is notoriously difficult. Once it’s embedded in a country’s systems it’s difficult to weed out. But a fresh approach is being pursued in Nigeria – with some startling results. Ordinary citizens are mobilising the use of technology and social media to produce evidence that’s used to hold officials to account.

Our research set out to discover whether the use of technology and social media by ordinary citizens to monitor infrastructure projects could result in more infrastructure projects being completed – and could also lessen corruption.

A version of this approach has been tried in countries like Peru and South Korea. Nigeria seems to be the first – at least on the African continent – to monitor infrastructure projects in this way.

Our research found, for example, that the camera feed showing the construction of the second river Niger bridge, and similar schemes by Tracka gave citizens the power to monitor infrastructure projects. It also increased transparency and could be used to hold the government and engineering firms that build infrastructure to account.

But we also found that there were challenges. For example, citizens needed data and power to monitor infrastructure projects. Neither was always available.

The approach

Monitoring projects has been used by firms and the government as a way to provide more transparency.

For example, research from Uganda shows that corrupt government officials were less able to siphon money for their own enrichment when citizens knew where money was supposed to go and could therefore monitor spending; the diversion of funds fell by 12% over six years.

Research from Kenya also showed that public monitoring of government projects reduced corruption by 20%.

In Nigeria, we investigated infrastructure projects that were monitored by citizens and compared these to infrastructure projects that weren’t monitored. We found that there was a positive link between citizens using technology and social media to monitor infrastructure projects and better completion rates and standards for the infrastructure projects.

Generally, when government officials and infrastructure building engineering firms knew that they were being monitored, they didn’t want to get caught out. In certain cases, citizens were able to engage with the ministry of works and their state governor and use social media to engage in discussions about the project.

By taking pictures of the proposed infrastructure sites and tagging their state governors or representatives in regular posts about the infrastructure projects, civic participation was encouraged. Although there was no often response in the first instance, the high visibility generated by social media and the threat of losing forthcoming elections often resulted in the infrastructure projects being completed. But this was only for projects that citizens could monitor – and there are too few of these. Even we struggled to find many.

Our investigations also revealed that frequent offline and online discussions created awareness about the infrastructure projects and helped citizens to suggest projects that would be useful for their communities.

Challenges to this approach

This approach is not without its challenges.

For example, citizens needed key information to monitor infrastructure projects properly. This included the type, cost, key stages and duration of the projects. Only then would they be able to compare what was actually happening before their eyes to what had been budgeted for so they could alert the relevant authorities as soon as there were discrepancies.

Mobile network technology and access to social media platforms are also needed to make this work.

There were also social and cultural issues. Some citizens didn’t want to engage with social media and technology for personal reasons. In addition, when evidence of corruption was reported by citizens, some saw this as a politically motivated attack. The result was that they lashed out instead of trying to solve the corruption being exposed.

Other challenges included:

- a lack of clear penalties for individuals involved with monitored infrastructure projects that not completed, or not completed to a decent standard;

- a lack of follow up by the relevant anti-corruption authorities; and

- not enough being done when there were clear cases of standards not being met.

Implications

Technology and social media can be used as effective tools by citizens to monitor infrastructure projects. But this isn’t enough on its own. It can only be effective if budgets are also made fully visible.

This would enable citizens to know what they are monitoring and what to look for. Citizens would be wise to demand such transparency: honest governments will have nothing to fear.

This points to the need for a comprehensive approach to tackling corruption. This would need to include transparency and offline and online citizen engagement. In this context, technology and social media could be used as complementary tools.

If African governments and infrastructure building engineering firms on the continent are really concerned about corruption and want to show that they have nothing to hide, they can use this approach to gain more trust from the citizenry.![]()

Tolu Olarewaju, Lecturer in Economics, Staffordshire University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.