Originally published by IPB here

By Paolo de Renzio, International Budget Partnership— Apr 17, 2018

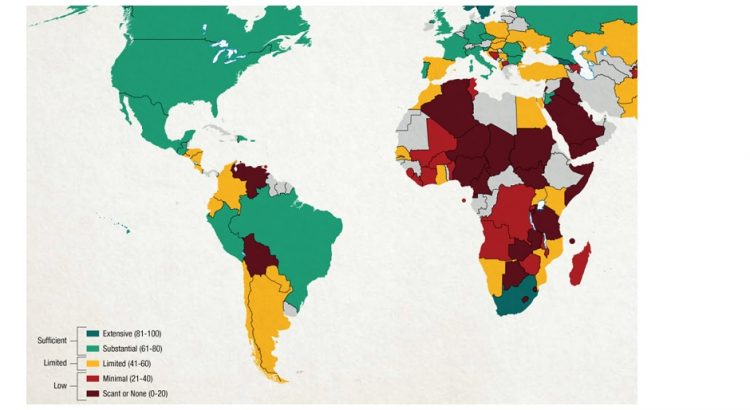

The Open Budget Survey 2017 recorded a global decline in average budget transparency scores for the first time since the survey’s inception. Nowhere was this decline more pronounced than in sub-Saharan Africa, in which 15 countries saw their Open Budget Index (OBI) scores drop by more than five points. A recent post examining this backslide attributes most of it to a reversal of previous practices, as a significant number of previously published budget documents were either not published, published late, or not posted on government websites.

Highlighting a lack of institutionalization of budget transparency practices as a potential cause for the reversal, the post’s authors emphasize the need for governments to “engrain” the publication of budget documents into standard public finance procedures and activities. They posit that institutionalizing transparency through, for example, laws and regulations, would make budget information accessible to citizens in a more regular and predictable manner.

- going beyond the inclusion of transparency provisions in legislation, and focusing on the implementation of the provisions;

- ensuring that broader budget reform strategies include transparency components and activities;

- using digital tools to disseminate budget information (for example, the creation of budget transparency portals); and

- introducing institutional measures to coordinate transparency efforts and ensure reform implementation, such as establishing dedicated units responsible for publishing budget information.

Based on these findings, IBP worked with the Collaborative Africa Budget Reform Initiative (CABRI) last year to survey African governments on the degree to which they had similar initiatives in place. Survey questions addressed: 1) the specificity of legislation concerning the publication of key budget documents; 2) the entities responsible for ensuring budget information is published – e.g., the existence of a dedicated unit within the finance ministry; 3) whether governments had a dedicated website/page for budget documents, and if said website was regularly updated; and 4) if government reform strategies or plans included key budget transparency measures. Finance ministry officials from 22 countries responded, 17 of which are covered by the Open Budget Survey. Among these, only one (Senegal) improved its OBI score significantly between 2015 and 2017.

While it is not easy to identify very clear linkages between Open Budget Survey results and institutionalization of budget transparency reforms from the limited information gathered from the IBP-CABRI survey, a few interesting cases stand out.

The two countries with the most significant decline in OBI scores were Botswana (-39 points) and Tanzania (-36 points). In each, governments either published various documents too late to be relevant for public debate or failed to post them online, despite both countries having well-functioning websites during the research period[i]. We were not able to ascertain any reasons for such delays and inconsistencies; however, it should be noted that Botswana’s institutionalization of budget transparency practices is very limited. Its public finance legislation does not contain specific budget transparency provisions, there are no government units directly responsible for publishing budget information, and budget reform strategies generally do not mention transparency as a priority. In contrast, in Tanzania the 2015 Budget Act has very specific provisions for the publication and dissemination of different budget documents and the public finance management (PFM) reform strategy includes a number of activities related to the promotion of public finance transparency. These reforms indicate that Tanzania is ahead of Botswana in institutionalizing budget transparency, but the implementation of the reforms is lagging, possibly due to political transitions after the 2015 elections and the lack of political will by the current government, which is seen as increasingly authoritarian.

Senegal is one of the most improved countries in regards to OBI score, as highlighted in the Open Budget Survey 2017 global report. Here, the government has taken clear steps to institutionalize budget transparency practices. They updated their legislative framework in 2012 in line with regional WAEMU (West Africa Economic and Monetary Union) directives, and their Transparency Code now includes provisions for the government to publish five of the eight key budget documents considered in the Open Budget Survey. The government’s budget reform strategy includes various transparency provisions, and the Cellule de Communication within the Ministry of Economy, Finance and Planning is tasked with ensuring that all budget documents and reports are published. Furthermore, the General Directorate for Finance has its own website where budget documentation is posted.

Other WAEMU member countries, however, provide interesting examples of how laws and regulations alone may not be enough to guarantee the institutionalization of budget transparency practices. Both Benin and Burkina Faso saw their OBI scores drop in 2017, despite having comprehensive transparency legislation, similar to that of Senegal. Both countries have also put a lot of emphasis on promoting transparency in their recent budget reforms (as a consequence, Benin actually started publishing two budget documents in 2017 that it had not published previously). However, the countries also went through some important political transitions — including the aftermath of a coup d’état in Burkina Faso and a change of government in Benin — right around the time when the Open Budget Survey research was taking place. These isolated events may explain the drop in the countries’ 2017 OBI scores, providing hope for future improvements.

Thus, to better understand how budget transparency practices evolve over time, and why they recently worsened in sub-Saharan Africa, more detailed measures of how the levels of institutionalization of such practices are useful, but often insufficient. They may help us explain some of the reasons behind Botswana’s regression or Senegal’s improvements, but for other countries they only hint at broader factors linked to the political and institutional context that may be at play. The relationship between a government’s overall political commitment to transparency, the way in which this translates into institutional reforms that shape the behavior of public officials, and how such incentives shift over time in response to changing circumstances is a very complex one, and a topic that deserves further attention and research.

[i] More recently, the Government of Botswana has been undergoing a comprehensive revamp of its governmental websites, leading to the website finance.gov.bw no longer being active.

These materials were developed by the International Budget Partnership. IBP has given us permission to use the materials solely for noncommercial, educational purposes.