Post written by Elizabeth Stuart, executive director of the Pathways for Prosperity Commission on inclusive technology. Originally published here

One of many puzzles in development is that increasing spending on health and education doesn’t necessarily deliver expected results.

To turn this on its head: Madagascar, Bangladesh and South Africa all have similar child mortality rates, but South Africa spends 19 times more than Madagascar and 13 times more than Bangladesh on healthcare.

Indeed this apparent paradox is one of the reasons why so many countries rushed to be part of the World Bank’s Human Capital Project, as they sought answers to precisely this question.

The Pathways to Prosperity Commission’s latest report is in part an attempt to provide a way through this puzzle by asking: what can technology do (if anything) to improve effectiveness and efficiency in health and education?

And because we’re a commission on inclusive technology, we also looked at whether tech can increase equity of access and outcomes.

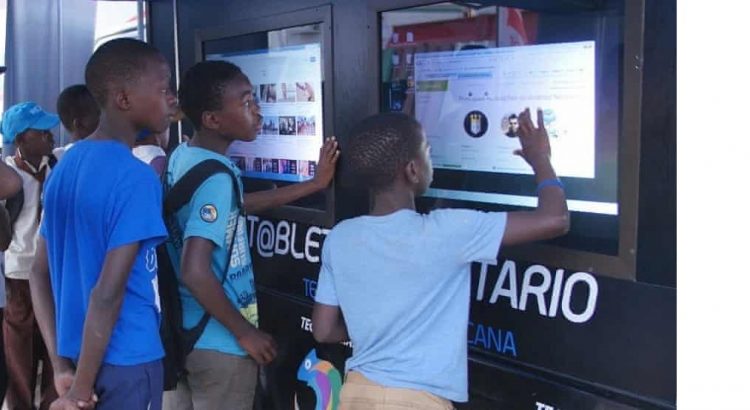

This is what we found: there are lots of sensible reasons to be deeply sceptical about technology in this area. History is littered with pilots that worked for a while, but weren’t sustainable, such as the One Laptop per Child initiative in Peru, which 15 months after it started, had no measurable effects on maths and reading scores, in part because teachers hadn’t been trained on how to incorporate the laptops into their teaching. And this isn’t limited to developing countries: there are also cautionary tales from the US.

In other words digital can’t be just seen as a simplistic fix to analogue problems.

But, where policy makers started with a proper understanding of problems that need to be resolved, and assessed delivery obstacles and constraints by analysing the whole system, rather than just asking why a tablet in a classroom is not delivering results, we found clear evidence that technology is already significantly boosting outcomes

In India, a study of a free after-school programme that introduced Mindspark, a digital personalised learning service, showed improvements in mathematics assessment scores of up to 38% in less than five months.

In Uganda, the web-based application MobileVRS has helped increase birth registration rates in the country from 28% to 70%, at the very low cost of $0.03 per registration – thus helping decision-makers track health outcomes and improve access to services. And mental health patients in Nigeria who received SMS reminders for their next appointment were twice as likely to attend as patients receiving standard paper-based reminders.

But – and this is where it gets even more exciting – we also found evidence to suggest that in the near future, digital technologies will offer the promise to transform not just results, but the entire system.

For example, careful and deliberate low-cost data collection will make it possible for health and education systems, supported by digital technologies and artificial intelligence, to continuously learn and improve both standard practice and decision-making by creating feedback loops at every level. Projects such as BID (Better Immunization Data) in Zambia and Tanzania give us a glimpse of how, with the right tools and training, frontline providers can use data to improve their work.

By capturing and processing large volumes of individual data, technology will make personalised diagnosis and intervention possible in both health and education. It takes skill, training and time for a doctor to develop a personalised treatment plan or a teacher to personally coach a student, but algorithms can use test scores and patient records to design and implement individual plans at little cost.

Systems could also become more proactive to ensure services get to the people that need them most. In the health sector, this is starting to emerge in programmes that use community data to identify high-risk patients for active outreach. In education, it will allow more precise targeting of pupils whose learning is lagging.

Source: World Bank (2019d), Gapminder (2019), Pathways Commission analysis. Note: This figure uses data from 2013. Expenditure is adjusted for purchasing power parity, and is reported as 2011 international dollars. The size of a circle represents a country’s population.

Source: World Bank (2019d), Gapminder (2019), Pathways Commission analysis. Note: This figure uses data from 2013. Expenditure is adjusted for purchasing power parity, and is reported as 2011 international dollars. The size of a circle represents a country’s population.

And digital technologies also offer the means to explicitly focus on those who are left behind by current service delivery models. In Mali, a proactive community case management programme initiated by the NGO Muso contributed to a remarkable 10-fold decline in child mortality; the success of free door step health care is amplified with a dashboard and devices for community health workers. In Uganda, a portable ultrasound device, called Butterfly iQ allows healthcare workers to use their mobile phone as a scanner, anytime and anywhere.

But these visions will not come to fruition automatically. For most, the right digital infrastructure will need to be in place. This means access to electricity and the internet and digital skills, as well as clear rules for data governance and privacy will be essential. New regulations, protocols and rules will need to be established to guard against privacy violations, data misuse and algorithmic bias. And most importantly, even the most effective system will not frontload outcomes for the poorest if there is no deliberate effort to do so.

Urging caution on deployment is perhaps counterintuitive for a tech commission, but having seen many of the quick fix mistakes of the past we know for sure what doesn’t work. But what we also know is that, done right, and delivered at scale, technologically-enhanced health and education systems and the right digital connectivity, could unlock benefits that could be genuinely distributed to all – and that would be revolutionary.

This article was originally published on the From Poverty to Power blog